Dozens of towns are passing MBTA-C plans. But how strong are they?

Upzone Update offers analysis of MBTA-C compliance efforts, produced by zoning expert Amy Dain and the staff of Boston Indicators. This week's article is by Amy Dain.

In the long run, we will assess the success of the MBTA Communities zoning law based on permits issued under the new zoning, homes built, places made and connected, and prices of housing. In the short run, we are puzzling together the diverse ways that municipalities are meeting the state’s new performance standards, and trying to figure out what it might all add up to.

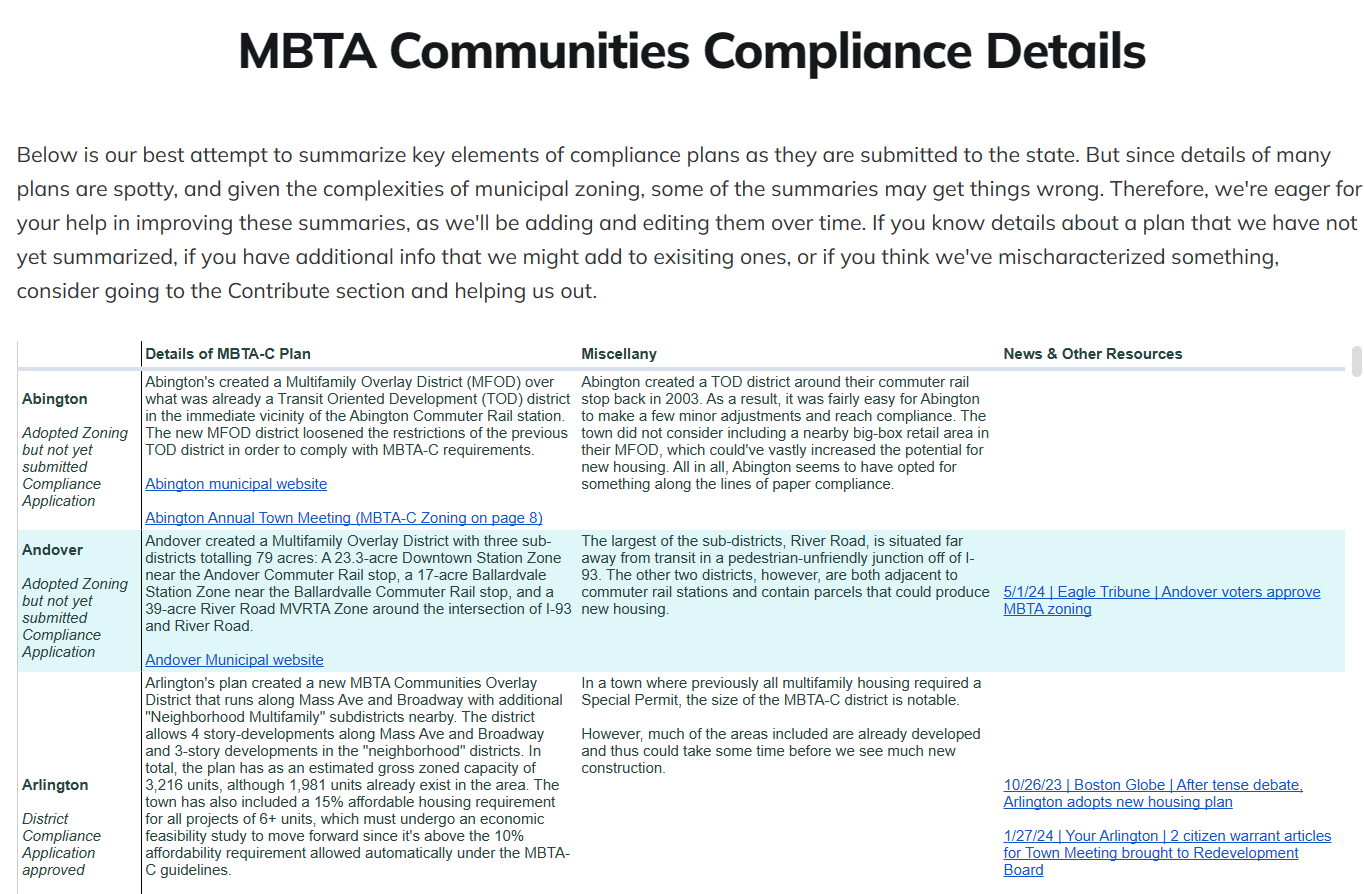

As a major part of the effort, Boston Indicators’ Lucas Munson is placing the puzzle pieces in a huge table of the 177 MBTA Communities. It includes summaries and analysis of local plans, as well as links to official documentation, PowerPoint presentations, and related news coverage. The table is a work in progress, like MBTA Communities zoning in general. Please help us fill the chart out, by sending additions, recommended edits, and your insights to upzoneupdate@bostonindicators.org or by filling out the form on the "Contribute" section of Upzone Update.

The Progress Report

The state’s primary strategy, right now, to overcome local zoning barriers that have caused a dire shortage of homes is implementation of the MBTA Communities zoning law. Is the strategy working? There are two parts to that question:

A) Are municipalities following through and revising their zoning laws to comply? B) How much new housing is projected to be allowed by the local zoning reforms?

Let's look at Part A first. Are municipalities complying?

So far, the vast majority of municipalities are complying. Approximately 60 municipalities have adopted zoning intended to comply with MBTA Communities. Many more are working on it. (See our Compliance Map for up-to-date details.) Twelve municipalities have voted down proposals: Hanson, Hopkinton, Foxborough, Marblehead, Marshfield, Middleton, Milton, Norwell, Rowley, Seekonk, Tewksbury, and Wakefield. Of these, only Milton is considered out of compliance, because its deadline, as a rapid transit community, was December 2023. The other communities still have months to approve new zoning. Some municipalities, like Wilmington, Lynnfield, and Hanover, are deferring their votes until after the SJC decision in the fall.

In the last few weeks many municipalities approved new zoning. Chelmsford Town Meeting approved MBTA Communities zoning, in a 125-19 vote. Westford approved it in a 402-88 vote. With a huge turnout, North Andover approved it, 535-253. Other recent wins include Wayland, Canton, Hull, Acton, Sudbury, Sharon, Whitman, Westwood, Walpole, Littleton (that had voted down its first proposal), Auburn, Rockland, Tyngsboro, and Medfield. (Municipalities rejecting proposals have garnered more media coverage than those approving zoning reform.)

About half of the 60-plus municipalities that approved MBTA Communities zoning submitted it to the state for compliance determinations. So far, the state has approved the zoning in Arlington and Salem as compliant, and in Lexington as compliant with conditions. The work to review the zoning against the performance measures is incredibly time consuming, and the stakes are high. Many local public officials are anxiously awaiting the determinations. Boston Indicators asked the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (EOHLC) about the status of the reviews.

EOHLC’s reply: “EOHLC is committed to a thorough review of every district compliance application and will continue to support communities who are developing zoning that works for their residents. We expect to announce additional compliant communities in the weeks ahead.”

As for Part B, what does this all add up to?

On the second question – what does all of the zoning add up to – it appears that the new zoning districts, overall, open up the zoning gates only in a small (yet important) increment. They might create room for 10,000 new housing units or tens of thousands of new units, but not hundreds of thousands. Some municipalities are coming into “paper compliance,” zoning over existing multi-family housing and recently constructed buildings. Most new districts cover some properties like this, while also covering properties that might actually be redeveloped. Some of the local zoning regulations technically allow multi-family housing while making its development unlikely, with dimensional and other requirements that don’t yield enough value in new construction to motivate the risk and effort of redevelopment.

It is important for policymakers to be aware of this, as full implementation of MBTA Communities will not by itself end the housing shortage, and the problem is profound. As Lt. Governor Kim Driscoll recently explained, “Nobody can keep up with these fast rising rents, and the lack of housing is impacting all of our communities across the Commonwealth. It’s hurting our economy, it’s hurting our workforce, and that means it’s hurting our state.” This is why policymakers need to support implementation of MBTA Communities zoning and do more.

Getting into the details

The MBTA Communities law gives municipalities a lot of flexibility in meeting its performance standards. Each local solution is unique. To grasp the big picture, it helps to look case by case at what municipalities are doing. Some of the municipalities featured here, like Bridgewater, are adding real capacity for new development; some are creating just a smidge of new capacity, like Burlington; and some are offering paper compliance.

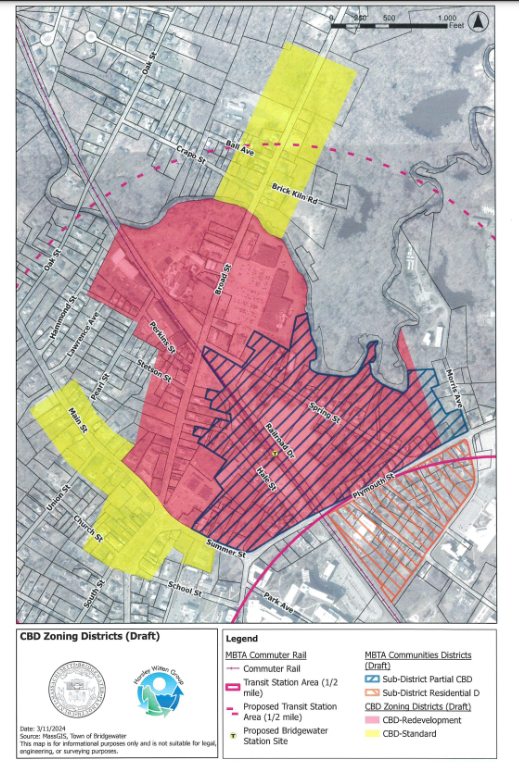

Bridgewater’s new zoning looks like real reform, in a great place for it. The state law propelled the town to approve the excellent new zoning; the deadline, with infrastructure funding at stake, motivated action. The new as-of-right zoning for multi-family residences, up to four-stories, stretches across numerous properties, a whole section of town, in a historic downtown area with restaurants, shops, civic buildings, a train station, and quiet side streets. The new zoning is getting paired with infrastructure investments, walkability upgrades, and transit reforms. Before the rezoning, multi-family development required special permits.

“All of these businesses would do better if more people were living here,” Bob Rulli, Bridgewater’s Director of Community & Economic Development, said this week pointing to low-rise shops along a main street. The residential density of Bridgewater is actually very low right now, for a historic downtown, with only about three residences per acre. Greater density will generate more foot traffic. Rulli expects a mixed-use project to come in for permit review shortly under the new zoning– for the redevelopment of a decaying bowling alley and restaurant, located between the train line and town green.

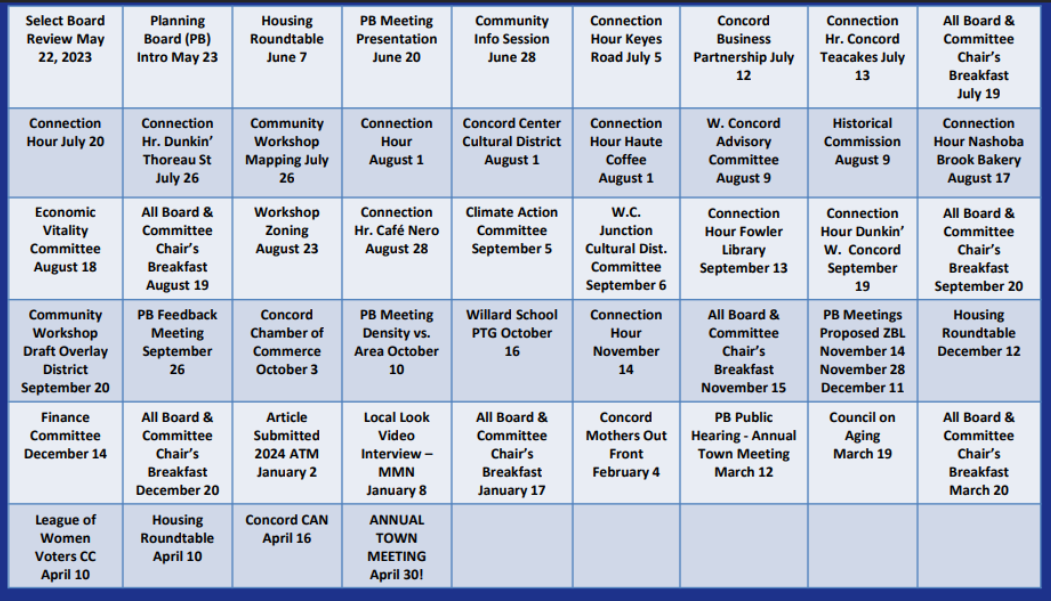

Concord adopted new zoning covering 31 parcels of land in five sub-districts--two near Concord Center and its train station, two near West Concord Village and its train station, and one by Route 2. Before the new zoning, all multi-family developments required either a special permit from the Board of Appeals or approval of Town Meeting. According to Elizabeth Hughes, Concord’s Town Planner, each of the five sub-districts has some real capacity for added housing. That the permitting is now as-of-right will reduce the cost and time of getting permits for homebuilding, and this is a win.

Yet, the zoning only allows three stories, 40 percent maximum lot coverage, 15 units per acre maximum density, and two parking spaces per dwelling unit (1.5 spaces for senior housing and affordable units) – requirements that highly limit the development potential of the 31 parcels. Moreover, many of the parcels were selected for having existing multi-family housing or new buildings that are unlikely to be redeveloped soon.

Astronomical home prices near Concord’s train stations and charming walkable historic centers reflect high demand for housing there. Concord’s recent reforms do not go far in serving that demand.

It is worth noting that this effort at incremental upzoning was incredibly staff-intensive. The implementation guidelines are highly complex; staff and citizens needed to learn the rules and choose districts and dimensional standards, out of endless possibilities. This is both an analytic challenge, and a political challenge. The planning department participated in over 50 meetings, events, and hearings, as shown in the following image:

Mansfield’s new zoning covers two sprawling privately-owned parking lots by the train station, near a historic downtown area. The two parcels are likely to yield a few hundred apartments once built out. This zoning gets Mansfield part of the way to meeting the MBTA Communities’ performance standards; Mansfield’s Town Meeting is scheduled to vote soon to rezone another large parcel that already has dense multifamily housing.

In the early 2000s, Mansfield embraced transit-oriented development by adopting an overlay zone where large mixed-use developments could be approved with special permits. The zoning resulted in hundreds of new apartments and retail space by the train station. Recently, the owner of one of the station parking lots applied for a special permit to build housing, but the Town rejected the application, since the access road to the property goes through residential neighborhoods. The new zoning now allows for the parking lot to be built out at even greater densities than the old special permit zoning allowed. The town is working to see a new access road built, to make the development feasible. Mansfield’s zoning for the parking lots now allows 30 units per acre as-of-right, and up to 60 units per acre by special permit.

On a Burlington Cable Access news show, BNEWS producer Sydney Boles summarized in an interview with the town Planning Director Liz Bonventre, “Maybe to dig a little deeper, if I’m hearing you correctly: No, this isn’t going to solve our lifecycle housing problem, it’s going to check a box with the state, maybe create some new units potentially.” Bonventre replied that it might ultimately lead to some more units.

Bonventre pointed out, “We have added multi-family housing where others have not.” Burlington’s approach, she explained, is to balance the “spirit of the law” which calls for more housing to address the shortage, with acknowledgement that Burlington has already permitted many multi-family projects. The implementation guidelines designed the initiative to let municipalities take credit for housing already built. Boneventre explained that they are threading the needle from both sides, responding to both housing advocates and people who oppose more housing.

An article posted by Burlington Cable Access Television summarized Burlington’s strategy: A team of government and civic leaders worked “to find six parcels that are already zoned for multi-family housing which could easily be overlaid for the MBTA Communities Act without much – or any – chance to the housing already on the site. An additional parcel would have slightly different properties and would encourage mixed-use development, with some housing and commercial purposes, between Middlesex Turnpike and Great Meadow Road.”

North Andover’s Town Meeting voted for two sub-districts, one at the North Andover Mall, and another at Osgood Landing. The Eagle Tribune reported that the Planning Board Chair explained, “We believe these sites are unlikely to be built in the near future.” The vice chair of the Zoning Board of Appeals, who advocates for more housing in the town, concluded, "The MBTA communities zoning act was designed to create more housing, this article does not do that. […] It is frankly astonishing to me that the state would agree to this.”

Patch reported that “Sudbury's approval, however, likely won't mean an increase in multifamily housing. The town created zoning overlay districts to comply with the law that cover the Meadow Walk and Cold Brook Crossing area — both existing dense housing developments along the Boston Post Road and Route 117, respectively.”

Patch is reporting a similar story for Wayland: “Like some towns, Wayland is complying with the law by adding multifamily zoning on top of existing multifamily developments, including Alta Oxbow, Town Center and the office/industrial park along the Boston Post Road at the Sudbury line. The town placed a fourth zone over Coltsway, a small condominium community with 18 residents off of Mainstone Road.”

Tyngsboro voted to approve MBTA Communities zoning. The Lowell Sun reports: “The largest of the three sites is on southeast Middlesex Road in an area which already has a number of apartment and condominium complexes. A second site is on land in Tyngsboro at the Pheasant Lane Mall parking lot. The third is on industrially zoned land behind the Olive Garden restaurant and some of that land is already permitted for that use.” According to the article, the town planner explained that the Pheasant Lane Mall site is the likeliest to be developed in the near- to mid-term.

In other communities, the planning and debating continue

The law is being hotly debated in Winthrop, among other places. Long-time Winthrop resident Tom Deredrian penned an op-ed in support: “As Winthrop faces the expensive threat of sea-level rise having more people in town will increase the reasons for state and federal grants to protect the town and keep property insurance rates down. Otherwise, Winthrop will have to increase property and other taxes to pay for whatever measures will be needed to keep our heads above water.”

Several committees and boards in Needham have been hard at work developing a new zoning plan, weighing different scenarios. The plan is to bring a proposal to a vote at the October Town Meeting.

Upcoming town meetings: Easton, Maynard, Swampscott, Mansfield.

We hope to report soon on new housing developments getting permitted under MBTA Communities zoning.

Keep sharing your updates with us! Email us at upzoneupdate@bostonindicators.org and make sure to check out the new features on our website.