End-of-year grab bag: Fair housing, implementation to-date, mixed-use development, and more!

Happy holidays to our readers!

This is the final biweekly issue of the Upzone Update. In 2025, the newsletter will come out less frequently as we pivot toward more in-depth analysis.

BY AMY DAIN

Fair Housing and Families

Many municipal voters are concerned about potential impacts of residential development on school enrollments, costs, and performance. Of course they are. A central task of local civic engagement is to look after the neighborhood schools. These concerns are raised again and again at zoning hearings, from Weston to Framingham, to Wrentham, to Lexington, and beyond.

Very often the concerns are misplaced. Housing advocates respond with data. School enrollments are dropping statewide. Most multifamily housing is occupied by households without school-aged children. Much of the unmet demand for multifamily housing is from seniors and young adults and small households generally. Look at Lexington’s pipeline of apartments and condos, approved under zoning free of restrictions on the number of bedrooms: a solid majority of units are one-bedrooms and studios. Advocates point out that growth can even bolster local budgets for schools.

But, what if reforming the zoning might actually lead to housing development… that leads to population growth… that strains the schools, escalates school costs, and brings down test scores? If this this a plausible scenario, is it okay for risk-averse voters to prohibit construction of multi-family housing? Empirically, city and town decision-makers do vote this way.

The system of municipal restrictive zoning is not fair for children from low-income, low-wealth households or renter households generally. The geographic segregation by class and renter/owner status, across municipal lines, disadvantages large populations of children. It undermines social mobility, exacerbates economic polarization, weakens the civic fabric, and widens the racial opportunity gap. It has even increased statewide aggregate education costs. All this on top of causing a housing shortage.

The situation calls for state-level planning, coordination, and oversight of residential zoning, in concert with planning for education and school building. MBTA Communities zoning reform has been a step in the right direction. The situation is also part of why the U.S. has Fair Housing laws.

The MBTA Communities zoning law requires cities and towns to zone for multi-family housing as-of-right without bedroom restrictions or restrictions on the ages of occupants. As-of-right means that developers won’t have to nix three-bedroom apartments to gain votes for discretionary permits. MBTA Communities spreads the responsibility to upzone across all communities, not to concentrate potential school costs on a small group of communities.

As for Fair Housing laws, Kristina Johnson, a municipal planner for the Town of Hudson and chair of Framingham’s planning board, has been anchoring local zoning deliberations with reminders about legal obligations to “further fair housing” for households with children. This should be standard practice at zoning meetings. Johnson shared her explanation in an email to the Upzone Update:

“It’s always prudent for a municipality to project and plan for future enrollment. With that being said, data on school enrollment in Massachusetts indicates a downward trend in enrollment numbers, and furthermore, that multifamily housing does not generate significant numbers of school-aged children

The Federal Fair Housing Act includes the obligation/requirement to affirmatively further fair housing objectives that do not create disparate impacts for protected classes. A protected class under the Federal Fair Housing Act is familial status, and I interpret that to mean ‘household makeup’ and ‘families with children.’ Following that logic, a zoning decision that considers school enrollment would be creating a disparate impact for families with children, which in my opinion is a violation of the Federal Fair Housing Act. Also, Attorney General Andrea Campbell has signaled her willingness to pursue a federal fair housing suit if zoning decisions, specifically for the MBTA Communities, have the effect of excluding people of color, families with children, individuals who receive housing subsidies, people with disabilities, or other protected groups.”

A regional housing shortage is not an acceptable policy solution to protect schools, manage municipal budgets, minimize traffic, or maintain the charm of places. Good, just, effective policy should advance these agendas while allowing housing construction. Both the state and municipalities should lead the way.

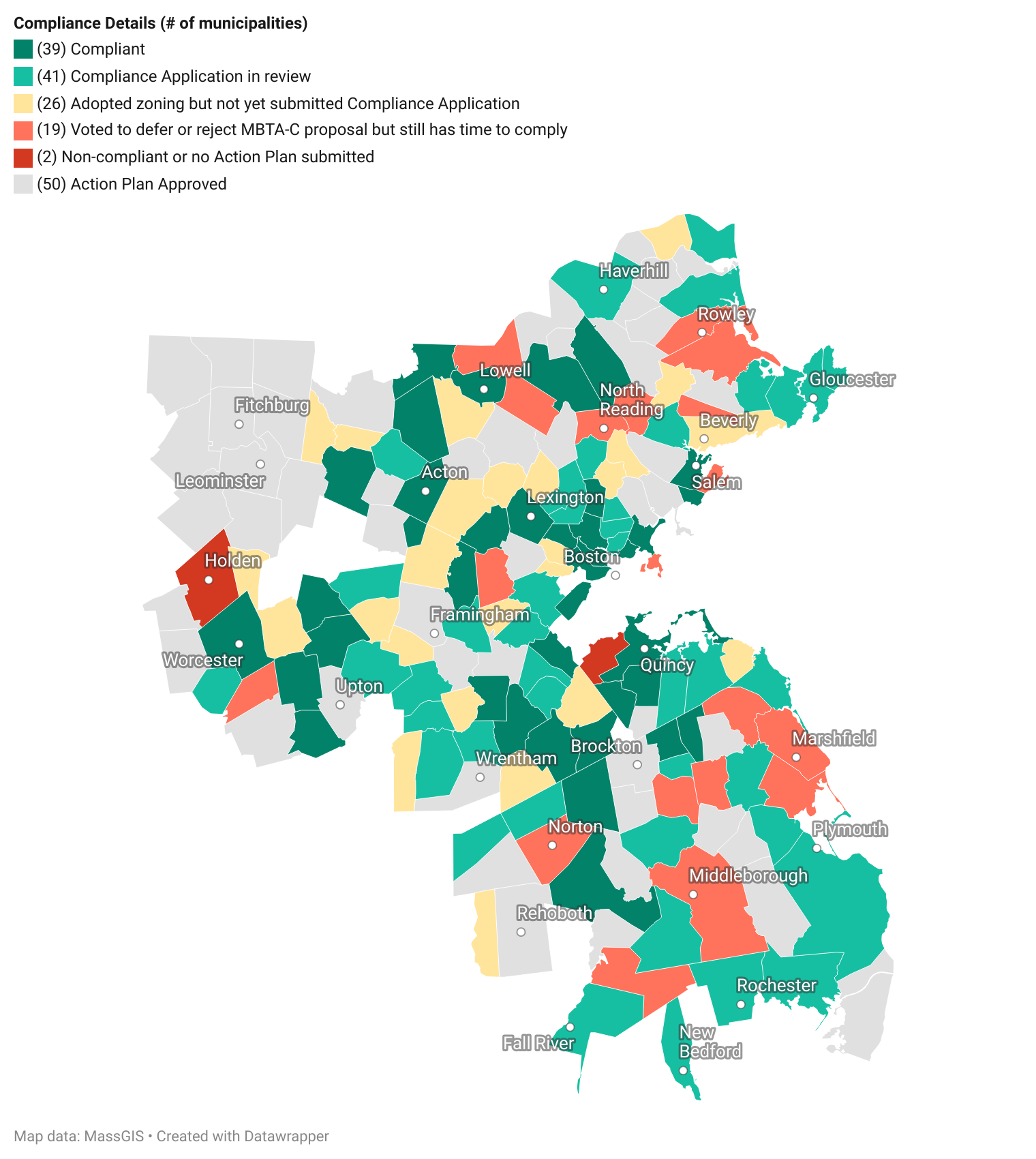

End-Of-Year Summary of Implementation

The MBTA Communities zoning law applies to 177 cities and towns. So far 115 cities and towns have adopted zoning to comply. Norwell, Billerica, and North Attleboro just voted yes. Most of the communities have a deadline to comply by the end of this month; 35 small towns have a deadline of the end of 2025.

It looks like forty communities will not have adopted zoning to comply by the upcoming deadline. Some of those have voted down proposals, as Halifax, Marshfield, Middleton, Wilmington, and Wrentham just did. Brockton and Framingham City Councils have been working actively to come into compliance, but will keep working on the task into 2025. Some communities have postponed votes. A common refrain at Town Meetings and City Council deliberations has been, “Wait for the Milton decision.”

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) could issue a decision on the Milton case any day now, or next year. There are numerous scenarios of how this could play out, both in terms of the decision and the ways that municipalities, EOHLC, the AG, and the state legislature respond.

Needham, Gloucester, and Shrewsbury recently adopted zoning to comply with MBTA Communities—but all three municipalities will hold a referendum on the zoning in 2025. Some residents of Lexington have been mobilizing to get the Town to revisit its MBTA Communities zoning requirements, under which approximately 1,000 new homes are now in the construction pipeline.

When Good News for Retail is Good News for Housing

Recent decades saw a surge of zoning reform to allow apartments and condos upstairs from first-floor retail, or on the same parcel as retail. According to a 2019 survey of zoning in Greater Boston, 83 of 100 cities and towns had zoning provisions for mixed-use development. Communities not in that club were, in most cases, the most restrictive of multifamily housing altogether, like Carlisle, Dover, Duxbury, Norwell, Stow, Wenham, and Weston.

For a time, to allow multifamily housing meant to allow mixed use. In many places, the only way to build multifamily housing was combined with retail.

This is great at locations where retail is hot; both housing and amenities get built together. Where retail isn’t hot, required inclusion of commercial space can be a barrier to homebuilding, or a cost driver. In some cases, retail was included in projects only because zoning wouldn’t otherwise allow housing. The new mixed-used building with first-floor vacancy became a familiar creature.

The MBTA Communities implementation guidelines do allow for mandatory mixed use to be a part of compliant zoning in existing village- or downtown-style areas. But, no more than 25 percent of the required unit capacity can be met by zoning for mixed-use-only development. This means that MBTA-served municipalities have to allow some standalone multifamily housing (with no retail requirement). This is smart.

But, with all of this as a preface, there is some excellent news for mixed-use development! Greg Ryan of Boston Business Journal reports that retail is doing far better than expected in Greater Boston. The region’s retail vacancy rate is just 2.2 percent, the lowest it has been in decades. Greater Boston’s housing density, high household income, and strong job base support the fundamentals of brick-and-mortar retail. It also helps that people working from home have been visiting neighborhood stores.

The folks behind the Trio development in Newtonville know this first-hand. Trio’s restaurants and retail are not only popular in the neighborhood but are also a draw for the residential tenants of Trio itself. Where retail is strong, a mixed-use approach can be a win for everyone. The improved retail market, in combination with already-adopted mixed-use zoning, should be a formula for more housing approvals.

History of the State Taking the Lead in Zoning Policy

Some opponents of MBTA Communities have argued that Massachusetts historically granted municipalities unconstrained power to use zoning. Aaron Sege argues to the contrary in this well-researched and well-written piece in Boston College Law Review. Sege presents a history of state statutes adopted in 1946 and 1959 that overrode local exclusionary zoning authority in different ways. Sege also points to Chapter 40B, adopted in 1969, that lets property owners bypass local zoning under certain circumstances to build mixed-income housing.

Sege does not mention the 1950 Dover Amendment, which also constrains local zoning power. Perhaps he omitted it because this amendment to the state Zoning Act was originally adopted to protect religious uses of land from local restriction, as opposed to addressing housing per se. But the Dover Amendment has been used for the permitting of housing built by religious and educational institutions, for religious and educational purposes. And recently, accessory dwelling units have been added as a protected use under the Dover Amendment.

Dover Amendment history: In 1949, the Roman Catholic Dominican Order wanted to establish a priory (a small monastery) on its 78-acre property in Dover, where the population was predominantly Protestant. The Dover Board of Selectmen turned down the permit application because the zoning prohibited educational organizations of sectarian nature in the district. Dover’s Zoning Board of Appeals then reversed the decision and granted permission. Many people saw the Selectmen’s decision as an act of discrimination against Catholics. Thousands of people demonstrated at the State House. The Attorney General spoke out.

In 1950, the state legislature passed the Dover Amendment to Chapter 40A, the state’s Zoning Act, to prevent municipalities from using zoning to prohibit the use of land or structures for religious purposes. Since 1950, other uses have been added to the Dover Amendment, including educational institutions, child care, and farming—as well as ADUs.

ADUs

EOHLC has drafted regulations for administration of the new ADU law. Please share your comments with the state by January 10. More info about the process is shared in this letter from Secretary Ed Augustus.

NEWS

Jay Luker, Lexington Town Meeting Member, wrote in an LTE to the Boston Globe, “Much like planting a tree, the best time to invest in transit was yesterday. Of course the second best time is now.” Not only is the traffic itself a problem, but fear of traffic is also behind Greater Boston’s housing shortage. So, he concludes, “Stop kicking the can down the road and invest in the MBTA.”

Mark Sideris, Watertown City Council president wrote in an LTE to the Boston Globe about Watertown’s successful rezoning for MBTA Communities, “We needed more than 1,700 units to comply with the MBTA Communities law. We have added zoning to allow more than 4,000 units in this area.”

Boston Magazine investigated the eviction crisis and reminds us why the effort to reform zoning is so critical.