Guest post: A survey of ambitious state policies from across the country

Upzone Update offers analysis of MBTA-C compliance efforts, produced by zoning expert Amy Dain and the staff of Boston Indicators. Scroll to the bottom for a listing of news coverage and upcoming events.

BY JOHN INFRANCA

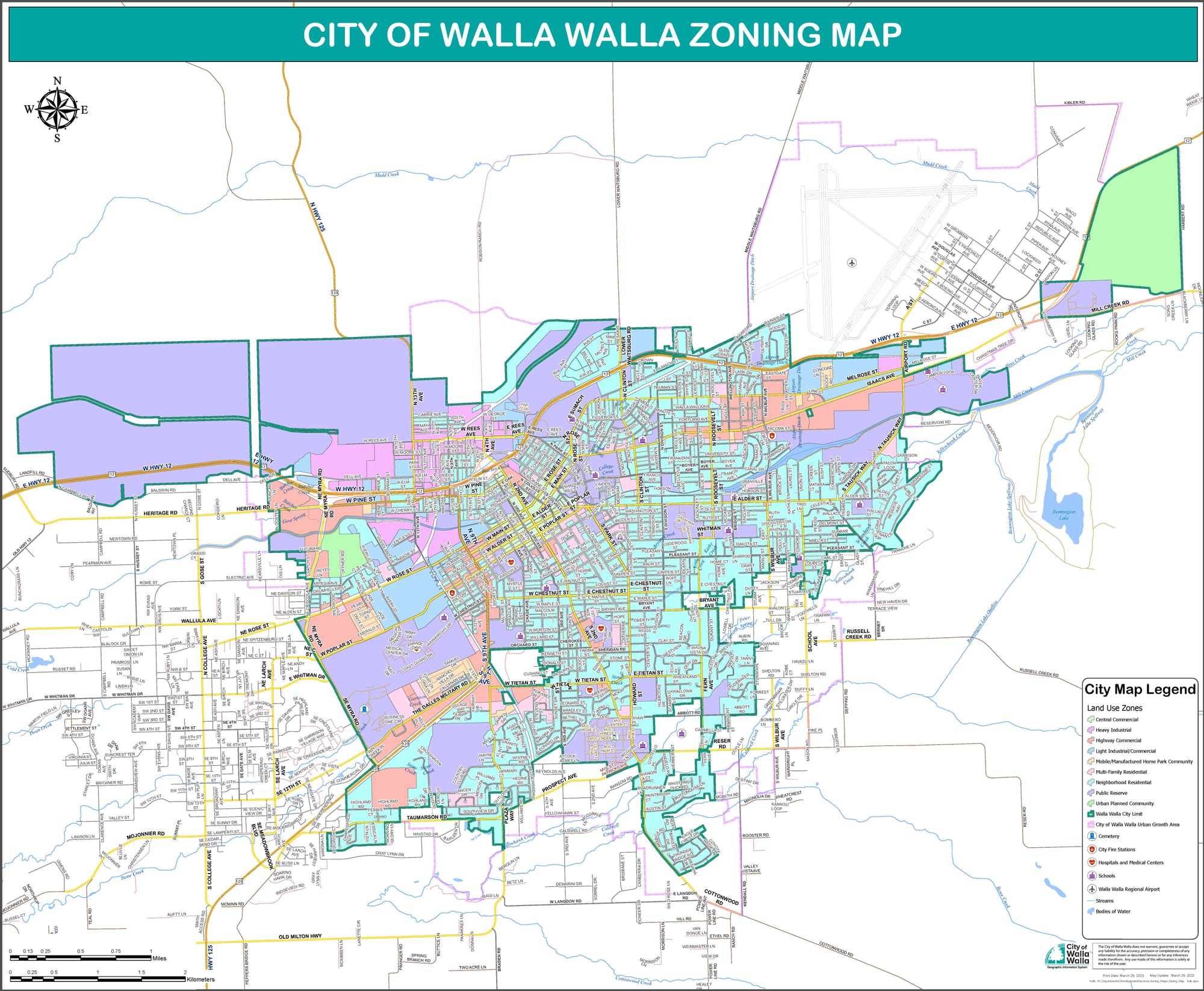

The MBTA Communities law represents a relatively modest reform that channels, rather than displaces or preempts, local decision-making. Other states have instead directly constrained local control, particularly around the regulation of single-family districts, parking mandates, and transit-oriented developments. Massachusetts should take note. It will take more than MBTA Communities to build the hundreds of thousands of new homes Massachusetts needs.

Massachusetts did recently preempt some local restrictions on ADU development. But several states have gone further. Idaho, Washington, and California have not only preempted local restrictions on ADUs but also prohibit homeowners’ associations from enforcing private restrictions that would prevent accessory dwelling unit development.

Washington also requires local governments to modify their zoning regulations to permit denser development in single family neighborhoods, including “duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, fiveplexes, sixplexes, townhouses, stacked flats, courtyard apartments, and cottage housing.” Cities between 25,000 and 75,000 residents must allow at least two units per lot on all residential lots, and four units per lot on lots within one-quarter mile of a major transit stop. Cities with populations over 75,000 must allow at least four units on all residential lots, and six units on all lots if at least two of the units are affordable. While cities retain some flexibility in the forms of housing they permit, they must allow at least six of nine designated types of middle housing.

California requires local governments, subject to some limitations, to permit homeowners to both split any single-family lot (so long as the newly created lots are at least 1,200 square feet) and build up to two houses on each of the split lots, allowing for up to four units on an existing single-family lot. Similar measures allowing the development of duplexes or quadplexes on lots statewide have become law from Oregon to Vermont.

A few states preempt local regulations on parcels near public transit. In Maryland, developments within three-quarters of a mile of a rail station that set aside at least 15 percent of units as affordable housing may exceed local density restrictions and the local jurisdiction “may not impose any unreasonable limitation or requirements” related to height, setback, bulk, parking, and similar requirements. In Colorado, local laws cannot impose minimum parking requirements for multi-family and certain mixed-used developments within one-quarter mile of transit. California similarly prohibits cities, counties, and any other “public agency” from enforcing parking minimums within one-half mile of a major transit stop.

Two California measures that became law in 2022 allow certain multifamily housing developments in districts zoned for office, retail, or parking uses. The Affordable Housing on Faith and Higher Education Lands Act, part of the nascent YIGBY (Yes in God’s Backyard) movement, allows religious institutions, as well as non-profit colleges, in California to build affordable housing on their land. Each of these measures effectively rewrites or overrides components of existing local zoning ordinances.

In addition to these measures that directly preempt local laws, some states require local governments to choose and implement a certain number of zoning reforms from a list of possibilities. Montana’s requires local governments to incorporate a minimum of five strategies for encouraging housing development. These strategies must be chosen from a list of 14 possibilities, which includes, among others, allowing duplexes (or triplexes or fourplexes) on all single-family lots, upzoning for more density near transit, allowing ADUs on single-family lots, eliminating or reducing minimum lot sizes or setback requirements, and allowing multi-unit developments on all lots zoned for office, retail, or commercial uses.

In sum, states across the country have sought to address the housing crisis by directly displacing local restrictions on homeowners’ control of their property. Viewed in the context of these reforms, Massachusetts’ MBTA-C represents a modest intervention in local zoning and one that retains significant local control. It merely channels the exercise of local power in furtherance of a vital statewide interest.

John Infranca, Professor of Law, Suffolk University

This short article is excerpted from John Infranca, Striking a Balance: Massachusetts’ MBTA Communities Law and the Channeling of Local Control (forthcoming, Virginia Environmental Law Journal (2025)), draft available here.

News & Articles

Compiled by Amy Dain

We are deeply saddened by the passing of Greg Bialecki, an extraordinary leader. Joe Kriesberg and Andre Leroux explain in a remembrance about Greg’s role in Massachusetts zoning reform and housing policy:

“Greg was the first and most powerful state official in a generation to prioritize zoning reform, up to that point considered by most to be a thankless, ‘impossible’ issue. He leveraged his platform to communicate to legislators and the public the ways in which local zoning constrained housing production. He convened municipal representatives, the real estate community, planners, and environmental advocates to try to resolve their differences. Although his efforts to forge compromise did not yield immediate results, his persistence elevated the issue and helped pave the way for the Housing Choices Act and the MBTA Communities Act that passed in 2021.”

IN THE NEWS

The Boston Globe offers a status report of MBTA Communities implementation. Nearly 50 cities and towns that face an end-of-the-year deadline have yet to adopt compliant zoning. The vast majority of communities that have voted on new zoning have approved it.

Andrew Brinker of the Boston Globe continues his in depth coverage of housing policy with a look at Lexington. He writes: “It’s also symbolic that the town leading the way is Lexington, with its median household income topping $200,000 and a single-family home price of around $1.6 million. It’s the sort of place where zoning rules have long been used to block new development, which has made the town more and more exclusive over time.”

It is interesting that Lexington’s inclusionary requirement (that 15% of homes be priced affordably for lower- and middle-income households) is working to yield many new affordable homes – nearly 150 so far in Lexington’s MBTA Communities zoning districts, according to Brinker. This is a notable success for a policy that cuts two ways.

Inclusionary requirements bring price diversity to areas that wouldn’t otherwise see it in the short term. A main purpose of zoning reform, after all, is to increase housing opportunities (affordability) for lower-income and lower-wealth households. But, as Scott Van Voorhis of Contrarian Boston points out, the policy can lead to rent inflation: “The developers are forced to make up for losses in the below-market-rate units, pushing rents higher than they would otherwise in the market-rate apartments in the rest of the new building or high-rise.” Also, where market-rate prices are not high enough, inclusionary requirements can make projects financially infeasible, inhibiting needed production.

Needham’s new zoning is going to town-wide referendum.

It looks like Gloucester’s new zoning is as well. Gloucester City Council passed new multi-family zoning by a 7-0 vote in October. Opponents submitted a petition to suspend the zoning and call for the City Council to rescind the zoning. City Council then voted 6-0 against rescinding the zoning, which meant the zoning would continue on to a referendum. The vote has not yet been scheduled.

MetroWest Daily News summarizes MBTA Communities implementation in the MetroWest region. Ashland, Bellingham, Hopkinton and Millis recently passed new zoning. Franklin, Holliston, Marlborough, Medway, Natick, Northborough, Southborough, Sudbury, Wayland, and Wellesley have also come on board. Framingham is working on it. Upton and Sherborn have until the end of 2025.

Jonathan Berk gives Watertown a Gold Star for its rezoning and planned upgrades of Watertown Square. Many communities have this dilemma, about what to do when through-traffic dominates a civic and commercial (and residential) center. Watertown is trying some new things.

The Lowell Sun explains Shirley’s rezoning, and Dracut’s zoning rejection. Reporter Today covers Seekonk’s rezoning.

The Gloucester Times covers opposition in Rockport.

Weston voted this week to reject MBTA Communities zoning.

The Boston Globe Editorial Board says that using tax dollars to block new housing is bad policy.

Newtonville, which hosts MBTA Communities-compliant zoning districts, is getting an upgraded train station. This is the big idea of transit-oriented development – upgrade infrastructure and add housing in walkable, amenity-rich, transit-served hubs. Streetsblog reports: “The $50 million project will replace the existing Newtonville station – a single platform that's accessible only from two long staircases – with a new, fully accessible station that will include level-boarding platforms for both tracks, elevators, and a bridge to carry passengers over the tracks to a new entry plaza on Washington Street.”