Is new housing a school budget buster? What does the research say? (And why you shouldn't worry too much anyway)

Upzone Update offers analysis of MBTA-C compliance efforts, produced by zoning expert Amy Dain and the staff of Boston Indicators. Scroll to the bottom for a listing of news coverage and upcoming events.

Cover article by Luc Schuster, Executive Director of Boston Indicators

Concerns about rising school costs loom large over MBTA Communities planning debates—or really any local discussion around building new housing. The fear is that an influx of new families will strain public services, particularly education, and that these costs will outweigh any economic gains and additional tax revenue. But what does the research say?

In general, studies show that in high-cost, high-demand regions like ours, reducing zoning restrictions to allow more housing is overwhelmingly beneficial. It generates construction jobs, stimulates local economies, lowers housing costs, and gives young families the opportunity to settle and raise children in the towns where they grew up.

Local research

But are there situations where the fiscal benefits of new housing are outweighed by local cost increases? Fortunately, local research sheds light on this question. In The Fiscal Impact of New Housing Production in Massachusetts, published in MassBenchmarks, Michael Goodman and Elise Rapoza gathered a representative sample of recent multifamily housing developments across the state, and using economic modeling, they compared the estimated tax revenues from new residents (including property, excise, and income taxes) against the costs of additional public services, such as MassHealth and K-12 education.

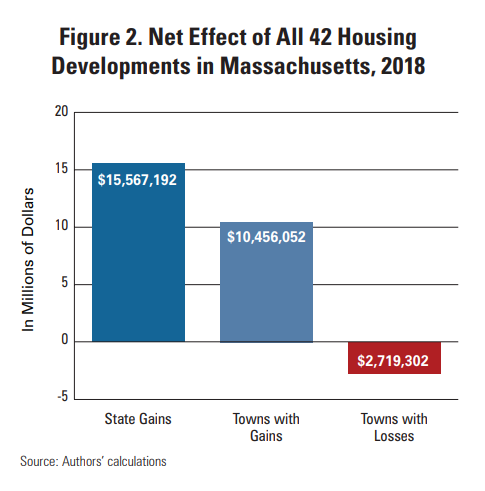

They found that, across 42 sampled developments, the fiscal impact was significantly positive. The state saw an annual net benefit of $15.6 million (in FY 2018), while municipalities experienced net benefits of $7.7 million. However, they noted a key caveat: In 12 of the 42 developments, local costs exceeded local benefits by a combined $2.7 million.

Communities more likely to experience net losses were those with schools already at capacity or where new housing brought in students with high special education needs. The state offers several grant programs to help offset these local costs, including Chapter 70 state aid, which was included in their estimates of net local costs. But the state runs other reimbursement programs like the Special Education Circuit Breaker fund, which was not included in their modelling of local costs, leading the impact of new local costs to be somewhat overstated. Either way, though, none of these state programs fully cover local expenses, and the level of state assistance varies based on a range of local factors.

The key takeaway from the analysis is that, at the state level, the net cost of new housing is overwhelmingly positive. Looking narrowly at the local level, the effect is usually positive as well. And in cases where local costs are greater than local revenue, a modest portion of the extra state revenue could be redirected to help those municipalities offset any shortfalls. Although the fragmentation of state and local governance can complicate this, the Commonwealth as a whole benefits tremendously from the growth that multifamily developments bring.

One limitation of this research is that it looks retrospectively at projects largely designed to minimize family occupancy—mainly consisting of one- and two-bedroom units—because that’s what could pass through local permitting. And there’s a meaningful step-up in the number of families with kids living in 3+ bedroom apartments compared to those living in smaller ones; only about 25 percent of households living in two-bedroom apartments in Greater Boston have kids under 18 compared to 40 percent of those living in apartments with 3 bedrooms. So, if future developments were to prioritize a greater mix of three-bedroom units or larger, the empirical evidence might change. When focused on concerns about school costs, this might be seen as a potential challenge. But if viewed through the lens of fostering a thriving, dynamic, and growing region, the fact that larger apartments tend to house more families with kids could be compelling evidence for building more of exactly this housing.

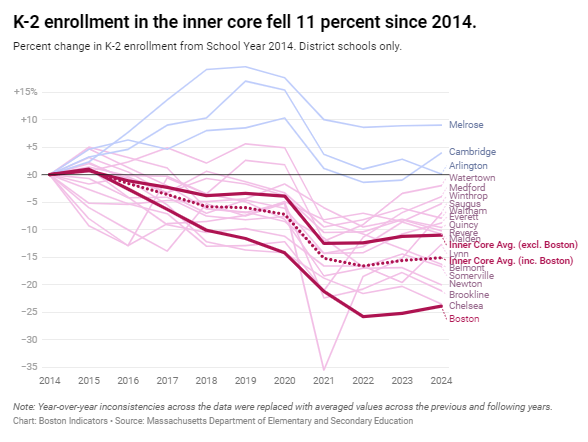

Another argument is that some schools in the region are losing enrollment, so a boost in the student population may not be such a bad thing. Although not a fiscal analysis, The Waning Influence of Housing Production on Public School Enrollment, produced by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC), analyzes the connection between housing development and school enrollment trends in Massachusetts from 2010 to 2020, finding that, despite some localized increases in enrollment, there has been no statistically significant link between new housing production and overall enrollment growth. In fact, some of the largest declines in school enrollment were observed in Developing Suburbs (-8.2 percent) and Maturing Suburbs (-2.5 percent), which contain many of the towns most resistant to new housing.

Moreover, recent trends in early grade enrollment since 2020 suggest that school enrollment may be declining broadly across the region. At Boston Indicators, we recently completed a short research series that found declines in K-2 enrollment across many inner-core communities in recent years. Since early grade enrollment is a strong predictor of future trends, this suggests that a growing number of communities may have increasing capacity to welcome new families. With excess capacity in many school districts, the marginal cost of adding new students is likely to be lower, making future multifamily housing developments potentially even more fiscally advantageous than previous studies have suggested.

National research

A key distinction often overlooked in discussions of fiscal impacts is the difference between multifamily and single-family housing. Multifamily housing tends to bring far more benefits—especially from an environmental standpoint. National research, such as Ryan Gallagher's study The fiscal externality of multifamily housing and its impact on the property tax, also finds important fiscal benefits of multifamily housing. Traditional views suggest that smaller housing units contribute less to the property tax base, shifting the burden onto larger homes. However, Gallagher’s research challenges this, showing that per-capita residential value, rather than total home value, is a more accurate metric for assessing property tax contributions. His findings reveal that per-capita values are often higher for apartments than for single-family homes. This means that, all things equal, communities can actually levy lower property taxes if apartments make up a greater share of their housing stock.

Broader social considerations and my personal take

Even if the fiscal impacts of building more multifamily housing were not convincingly positive, there would still be a compelling moral case for building more housing. Creating a more inclusive and welcoming region has tremendous value on its own, and we should not be held captive by the notion that every new housing unit must pay for itself. Families with children are integral to the vibrancy of any community, but in recent years, we’ve seen increasing domestic outmigration to lower-cost parts of the country, driven by young families with kids. These trends sap our communities of dynamism in the near-term and risk creating workforce issues over the longer-term as our population ages.

Further, the expectation that any individual project be net fiscally positive runs counter to the social contract. My two children currently attend public schools, and it’s certain that the cost of their education far exceeds what we pay in property taxes. But before they were born, this calculation was likely flipped, as it should be. This is the essence of the social contract: It is about shared contributions and mutual support. For every new unit occupied by school-age kids, there’s someone else making up the difference.

While new housing may, in some isolated cases, lead to additional local costs, this concern has been way overstated. And in many places, new housing construction is exactly the sort of strategy we need to strengthen the local tax base and fend off school closures driven by enrollment declines. We are fortunate to live in one of the most prosperous regions in the country, but I worry that our success has made us complacent, leading us slowly into a period of managed decline. We’ve gotten more resistant to change and less ambitious about the future. Yet, it’s precisely this wealth that also gives me confidence: We have the resources to absorb any marginal short-term costs that new housing might bring, all in the pursuit of a creating more dynamic, diverse, and thriving region for the next generation.

News & articles

Compiled by Amy Dain

Some people get information from e-newsletters. Far more people glean info from short videos shared on social media. So, Mass Housing Partnership has produced a series of short videos featuring compelling testimony given at public hearings. Here's a sample. Check out the rest on their YouTube page:

Almost half-way there

There are 177 MBTA Communities. The half-way mark will be passed once 89 municipalities vote to reform zoning to comply. So far, 82 have made the move.

The most recent zoning reformers: Natick, Needham, Marlborough, and Holliston.

Natick Town Meeting voted 85-15-1 to rezone an area by Natick Center. Town Meeting Member Jeff Alderson said at the Meeting, “Sometimes towns need a bit of a nudge to do the right thing.”

Needham Town Meeting approved new districts covering approximately 93 acres, where a density of 35 homes per acre will be allowed, at heights ranging from 3 to 4.5 stories. The district includes parts of Chestnut Street, Hillside Avenue, Crescent Road, and Hillside Avenue. Needham’s assigned zoning capacity target is 1,784 housing units; the new zoning accommodates a capacity of 3,300 units. Green Needham projects that this will put more customers in walking distance of businesses, encouraging local shopping and less driving.

Norton and Ipswich voted to postpone their votes on zoning reform. At Ipswich Town Meeting, town leaders presented the endorsements of the planning board, select board, school committee, and finance committee. Minority opinions from a few of those boards were also shared. A few speakers suggested that the Town should defer its vote on zoning reform until after the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court to issue a decision on the Milton case. Town Meeting then voted 295-294 to postpone the vote.

Many other municipalities are now working to craft zoning plans to comply with MBTA Communities. After a public hearing that ran late into the evening, Framingham’s Planning Board approved a zoning plan to forward to City Council for final decision-making. In September, Framingham’s Planning Board proposed new multi-family districts for four separate areas, including parts of downtown, Saxonvile, Nobscott, and Speen Street. The proposal allowed for 30 units per acre. At the latest hearing, the Planning Board adjusted the densities allowed in Saxonville and Nobscott to 15 units per acre, and expanded the district at the Staples headquarters to cover more acres. According to the state’s implementation guidelines, only 40% of Framingham’s MBTA Communities zoning capacity needs to be near the train station (which is in downtown Framingham); the Planning Board favored a strategy of distributing districts across different parts of Framingham.

Peabody, Duxbury, Beverly, and Rowley have made local news for their zoning reform efforts. There is a petition drive in Gloucester to bring the new zoning to referendum.

But actually, MBTA-C is way more than half-way there

It is easy to assess progress by counting how many municipalities are complying. But another, wonkier metric is even more important: zoning capacity. This is a measure of how much housing can be accommodated in full buildout of districts. MBTA Communities are way past the half-way mark in approving zoning capacity. This is because the 82 communities (that have gotten to yes) represent far more than half of the assigned zoning capacity.

The state’s implementation guidelines assign each municipality a unique zoning capacity target. The capacity number is calculated as a percent of the number of existing homes in a municipality. Rapid transit communities have the greatest responsibility, with their targets set at 25% of existing units. Commuter rail communities come in next at 15%. Then the adjacent municipalities only need to achieve 10% and 5% based on certain criteria.

Last year, Newton met its deadline to comply, adopting zoning districts with a combined capacity that surpassed Newton’s target of 8,330 units. Sherborn’s deadline to zone for just 78 units is still more than a year away. In a basic count of municipalities, Newton and Sherborn are equal parts. But in the effort to address a regional housing shortage, while bolstering public transit, Newton plays a role many times bigger than Sherborn. More high-capacity communities have already rezoned than communities with lower capacity targets have.

...And also just the beginning

Zoning capacities may be a wonky concept, but homes are where the heart resides. In the count of homes permitted and built, this initiative is just getting started. In this aspect, Westford is making the news.

The state implementation guidelines assign Westford a zoning capacity requirement of 924 homes. The town of Westford understood the assignment, and then some. This past spring, Westford Town Meeting overwhelmingly approved zoning for districts with an estimated capacity of almost 5,000 units. Greg Ryan reports in the Boston Business Journal, “In so doing, Westford joined the ranks of communities like Lexington and Somerville that have embraced the mandate.”

Reasons cited for the new zoning include the dramatic drop in demand for the town’s office parks, the need to grow the local tax base, and a widespread preference to concentrate new development in existing commercial areas. Westford’s concept is to make the Technology Park into a cohesive walkable, bike-able residential neighborhood.

Now the largest single project to come through MBTA Communities zoning is in Westford, a plan to build 530 apartments on what has been an industrial site.

Lexington is on its way to gaining another big project, Banker & Tradesman reports. This one is for 319 apartments, replacing three office buildings, at the Militia Drive office park, near town center. Lexington’s new zoning includes 12 districts spanning 227 acres.

Abby Patkin of Boston.com offers an overview and analysis of which towns are seeing homebuilding, on the other side of rezoning. She quotes Lexington Planning Director Abby McCabe, “We’re providing the housing, but we really need the MBTA to come forward with more of the public transportation.”

Other news

The Milton case has raised the question of legislative intent regarding options for enforcement of the MBTA Communities zoning law. So, MassINC’s CommonWealth Beacon investigated the question too, turning to Senator Brendan Crighton of Lynn who spoke for the bill on the Senate floor. Senator Crighton explained, “We had been talking about this for a long, long time. But certainly, when we pass a law, the intent is for it to be enforced. And, historically, that’s what the attorney general has done.”

On the topic of grants, Patch reports that the state’s $210,000 Coastal Resilience Grant to Marblehead could be in jeopardy if the town fails to comply with MBTA Communities by the year-end deadline. The Marblehead Select Board opted not to schedule a special town meeting in December.

Grace Ferguson of New Bedford Light offers an excellent overview of land use issues that New Bedford City Council is considering, including MBTA Communities districts, ADU zoning, parking, and permit approval processes. Right now, site plans for all multi-family projects have to be reviewed by the planning board. There is a proposal to allow three-family buildings by right, without site plan review. Buildings with four to six units would get site plan approval from the administrative planning staff, but not the planning board, which only meets monthly. Bigger projects would still go to the planning board.

If you are new to MBTA Communities zoning, check out Boston.com’s explainer.

The Harvard Crimson reports that the Cambridge Community Development Department presented recommendations to City Council to zone for up to 18 stories in Central Square. Former City Council candidate Dan Totten is quoted, “On one level, they’re the ideal place to build this new tower. On the other level, this is a cultural institution, right? It’s a paradox.”