Maximizing MBTA Communities by minimizing lot sizes

Upzone Update offers analysis of MBTA-C compliance efforts, produced by zoning expert Amy Dain and the staff of Boston Indicators. This week's article is by Amy Dain.

This week: a closer look at minimum lot sizes, an update on the Milton SJC case, and many new and exciting reports. Scroll to the end for a fun little story as well!

When it comes to lot sizes: How low can you go?

Dimensional regulations are not all loved alike. Some, such as building height limits, excite passions. Others, like minimum lot sizes for multifamily housing, take up table space (in zoning’s tables of dimensional regulations) without igniting debates. Here I will give multifamily lot minimums some due attention, but not much love.

Minimum lot sizes, also referred to as minimum parcel sizes, have long been a barrier to multifamily construction. Municipalities have required 10 or 20 acres of land, or more, for eligibility to build condos or apartments, where such large parcels are rare. Even five-acre or three-acre minimums are hurdles in many thoroughly subdivided places. And actually, the same goes for one-acre or ¾-acre minimums, or even 1/5-acre minimums—say 8,000 square feet.

Neighborhoods of smaller-footprint buildings distributed across small properties represent an ideal of livable, walkable urbanism, especially in historic suburban centers, where this is the built legacy. Greater Boston is blessed with thousands of pre-zoning triple-deckers built on lots smaller than a half-acre. Requiring large lot sizes encourages developers to consolidate parcels and build larger structures, instead of the small buildings of fine-grained urbanism. Scale can bring down costs per unit, and should be an option, but not a requirement.

Sometimes minimum lot sizes slip suavely into codes, just assumed to be a best practice, since they are so common. In some cases, proponents of minimums have suggested that larger-scale developments promise better quality. At some public meetings, people have commented that they’d prefer to discourage small-scale rental development, such as triple deckers.

The MBTA Communities zoning law and implementation guidelines are prompting many municipalities to shrink their lot size minimums for multifamily housing, or to ditch the minimums altogether. According to the state’s method for assessing compliance, properties that are smaller than the minimum lot size won’t be counted toward a municipality’s assigned zoning capacity, no matter that they are in a qualifying district and could be consolidated to make way for multi-family housing.

Several MBTA Communities, like Arlington and Andover, are requiring no minimum lot size for multifamily housing in their new districts. It can definitely be done, with no downside.

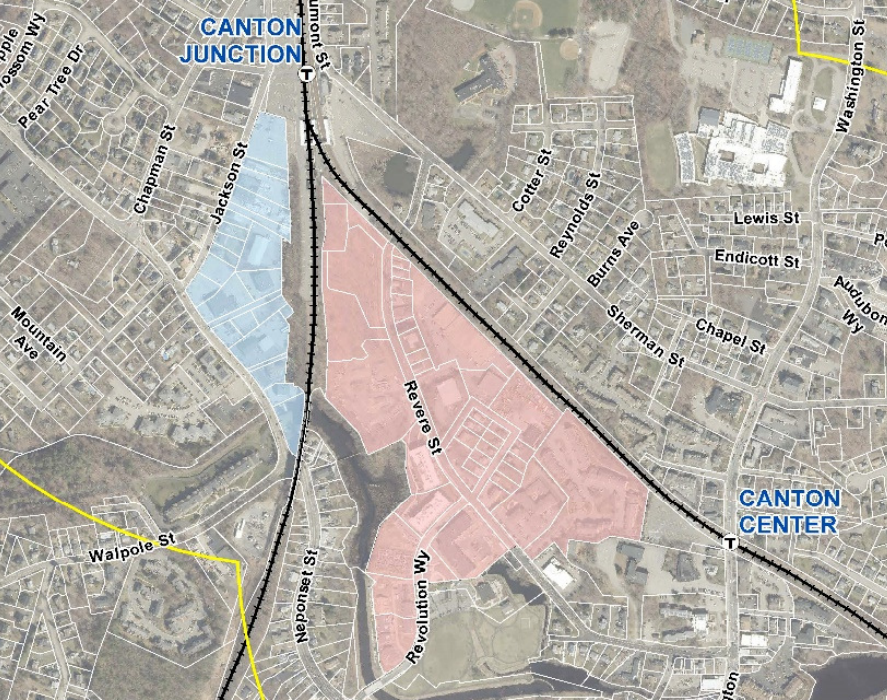

Unlike Arlington and Andover, Canton’s new MTBA Communities zoning includes a one-acre lot size minimum. Canton’s minimum means that a few smaller parcels in its district near Canton Junction Station cannot be developed under the new zoning (unless they are consolidated). In many communities, people argue against allowing big buildings, but apparently some people prefer bigger buildings to small multi-family housing.

Framingham has included a minimum lot size of 8,000 square feet in its proposed MBTA Communities district along Waverly Street (marathon route) near Framingham’s handsome walkable downtown and train station. (An acre is 43,560 square feet.) The requirement would disqualify a few 5,000 square foot properties, until or unless developers consolidate them. There’s still time for Framingham to lower the minimum, or discard it. Waverly Street is an excellent location for multi-family housing of varied sizes, little triple deckers or triplexes included.

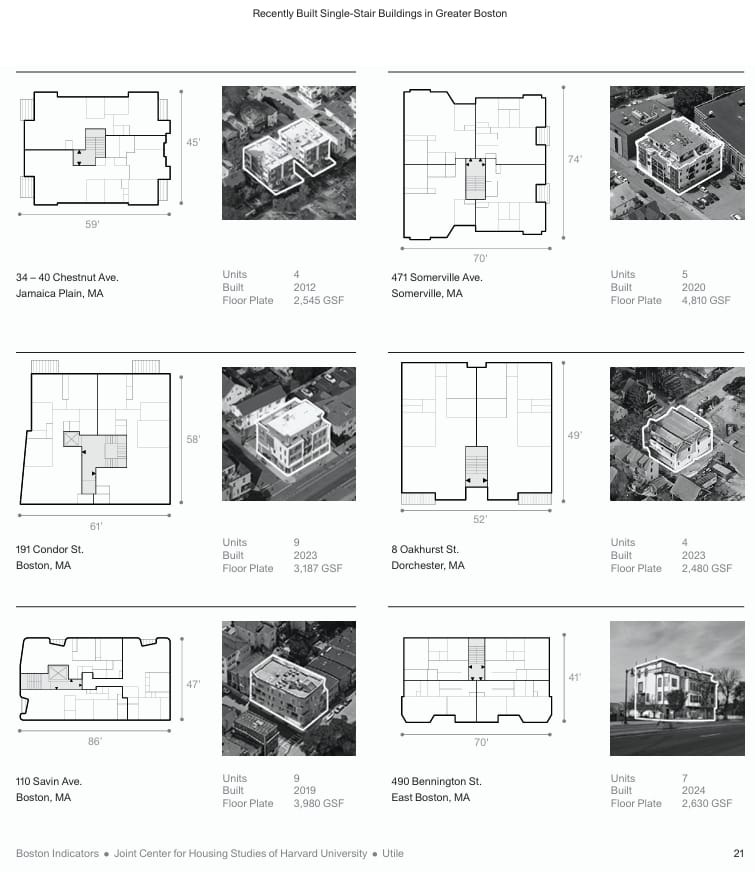

Let’s Legalize Mid-Rise Single Stair Buildings in Massachusetts

The building code in Massachusetts requires two separate stairways in buildings taller than three stories or containing more than 12 units. Not only is this requirement undermining production of mid-scaled (“missing-middle”) housing, hampering good architectural design, and driving up costs, the requirement is also unnecessary for protecting human safety.

Boston Indicators, Utile, and the Joint Center for Housing Studies teamed up to produce a compelling report on the issue. Watch the release event here.

This is such an important reform to pair with the MBTA Communities zoning law, as it will make feasible the development of more buildings under the new zoning. The reform will also improve building design, the look and function of places.

The Milton Case

On a rainy Monday morning, at an 1894 courthouse boasting classical columns, pediments, arches, and wood-paneled courtrooms, six justices of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) directed their attention to the MBTA Communities zoning law. They grilled two lawyers with hard questions, in the weeds of case law, statutory language, and procedure. It was focused and fast, all taking a total of one hour. The lawyers represented the Office of Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Campbell and the Town of Milton. They had no “phone-a-friend,” no panels of experts to confer with. This is why law school professors use the Socratic Method in the classroom.

Now the public will wait for weeks or months for the decision. What does it all mean?

First of all, we know what the case was not about. They were not deliberating whether there is a housing shortage and an affordability crisis, caused significantly by restrictive zoning. There is. The argument was not over the state’s authority to lead on zoning policy. It has that authority. They did not debate the merits of the policy approach, nor delve into the content of the state’s implementation guidelines for the law.

The case focused on details of the specific statutory language of the MBTA Communities zoning law and the Zoning Act in which the new law is embedded. One question was whether implementation guidelines can be considered as requirements, and if so, what the procedure should be for making the guidelines into requirements, and then whether the procedure the state followed in adopting the guidelines was sufficient toward those ends. In the MBTA Communities law, the legislative branch directed the executive branch to “promulgate guidelines to determine if an MBTA community is in compliance with this section.” The case also focused on the authority of the Attorney General and Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (HLC) to enforce compliance with the law and with the associated implementation guidelines.

If the court decision favors the Attorney General, this will facilitate ongoing implementation of the MBTA Communities law. Some municipalities have been waiting for the decision to pass their own local reforms. Questions do remain about how the Court, EOHLC, and AG will address non-compliance, in this scenario. If the court decision favors Milton, then that’s a speed bump in zoning reform. Capacity and support for zoning reform have been growing, so pro-housing leaders will find ways forward.

The case has garnered tons of media coverage, for example, in the Boston Globe, Banker & Tradesmen, WBUR.

Celebrating progress

Last week, the Healey Administration held a press conference in Somerville to celebrate the progress of implementation of the MBTA Communities zoning law, and to announce a new fund for infrastructure to support housing development in new multifamily districts. It was a moment to appreciate all of the work that has been done, and to get press coverage before the Milton case was argued at the SJC. The Administration announced that 75 communities have passed zoning to comply, and many more are working on it. Also, the state issued positive determinations of compliance to 33 municipalities. More municipalities will be submitting their applications for determinations of compliance soon.

Scott Van Voorhis, who writes Contrarian Boston, took the contrarian position in an article for Banker & Tradesman. He suggests our pols “ditch all the happy talk.” There’s a housing crisis, and local reform has been both slow and marginal. He reminds readers that many municipalities are going the route of “paper compliance.”

Other News and Ideas

Pioneer Institute’s Andrew Mikula wrote a report filled with case studies of municipal implementation of MBTA Communities zoning. Among other findings, he writes, “Many communities concentrated their 3A zoning districts in areas with existing commercial development or multi-family housing complexes, thus avoiding encroachment on low-density neighborhoods and minimizing the number of net new units able to be created.”

In Banker & Trademan, Jonathan Berk asks that people make a simple change in the way they talk about new housing: “We Bay Staters need to move away from referring to housing and new neighbors as a burden that needs to be mitigated and towards talking about them as benefits that our region cannot survive without.” Branding matters.

USA Today asks if zoning is the civil rights issue of our generation.

Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association (CHAPA) has mobilized business leaders to launch a new “Our Massachusetts” campaign. Jon Chesto has the story

Framingham’s Planning Board will hold a public meeting to discuss proposed zoning on October 17, at 7:00 pm. The City Council will hold a public hearing on the proposed zoning on October 29th.

Southborough, Gloucester, and Amesbury voted to approve MBTA Communities zoning. East Bridgewater, Middleborough, and North Reading voted it down.

Reward for scrolling to the end

Here’s a bonus story on the topic of lot sizes, for people who love land use policy and history.

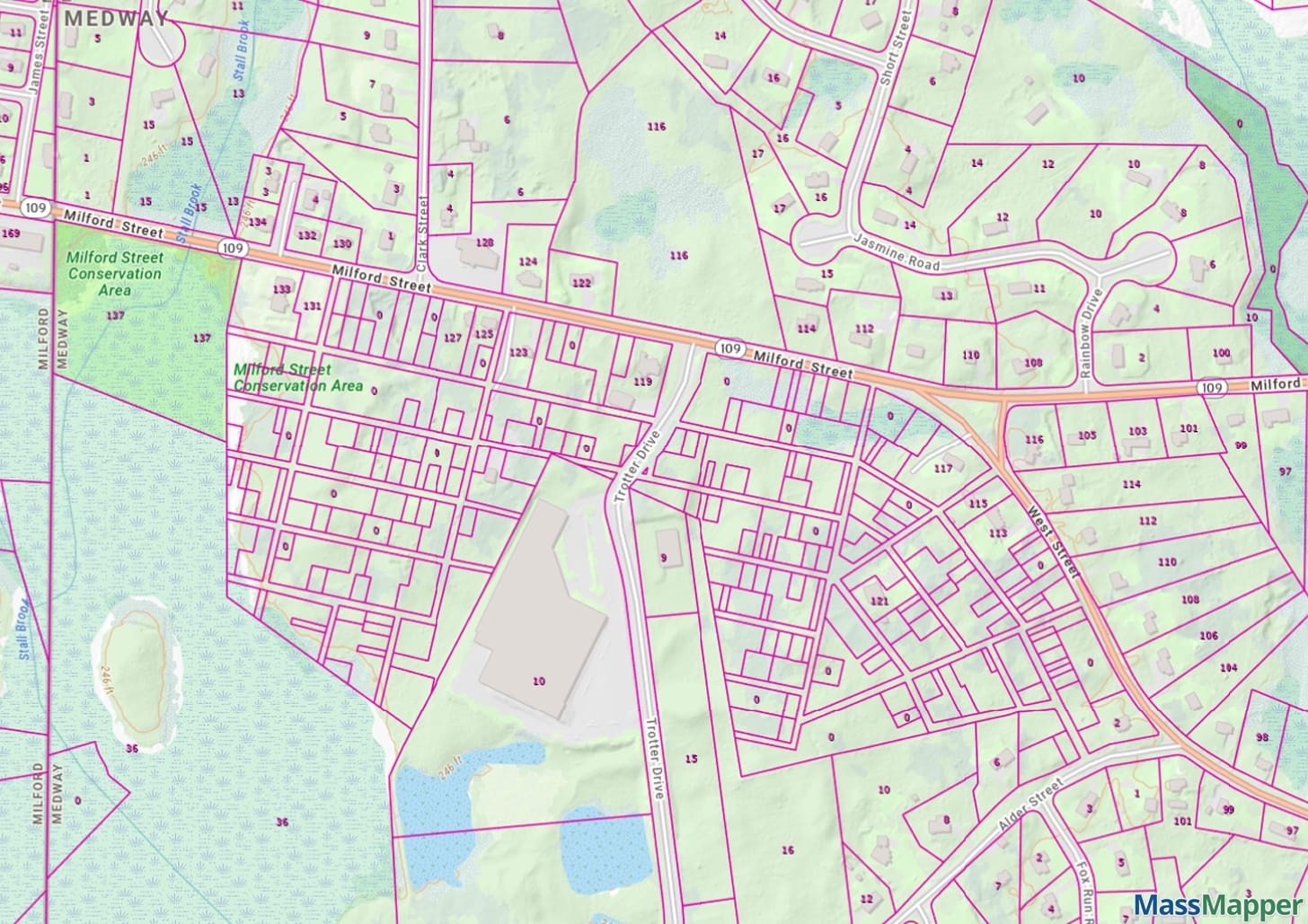

In the 1920s, Millis soda company Clicquot came up with a promotion to award little parcels of land in Medway to people who got winning bottle caps. Cliquot awarded more than a thousand “bottle cap lots,” small and awkwardly shaped. They averaged 1,600 square feet in size.

Nearly a century later, the bottle cap lots were a land use planner’s headache, so many useless lots and so many scattered owners. As some owners stopped paying taxes on the land, the town could consolidate many parcels, but not enough. By the 2010s, the state was getting involved, rather than leave valuable, buildable land, served by sewer, near highways and opportunity, undeveloped.

Bottle cap lots with frontage on existing roads have now largely been aggregated and built on with single family homes and businesses. The Redevelopment Authority is still working on aggregating the other parcels.

**Note, this strange history is not a reason to require minimum lot sizes for multifamily housing. Any property subdivided for a multi-family building would necessarily be big enough for a building’s floorplate as well as setbacks. The lot size minimum, for multifamily housing, would be extraneous for ensuring that lots remain big enough for building.