Meaningful or marginal?

By Amy Dain

One question reverberating through many MBTA Communities deliberations is whether the new municipal zoning rules should go beyond the state’s minimum requirements or not. For some municipalities, it is a question of meaningful compliance versus paper compliance.

So, for example, in Brookline, it was possible for the town to meet the state requirements by drawing new zoning districts over existing multifamily housing, basically legalizing what exists on the ground, but not allowing much new housing to be built. In other words, the town could have come into compliance, without actually taking part in the state’s effort to address our housing shortage. This was Brookline’s “fallback option,” if meaningful reform were to have failed.

But, Brookline voted for meaningful compliance, a scenario that involved approving the “fallback” zoning, plus additional zoning, significantly along Harvard Street. Some advocates had hoped for Brookline to allow even more housing.

In Newton, the scenario of “minimum compliance” that ultimately passed does offer more than paper compliance. The new zoning districts allow for many properties to be built with more housing units than currently exist on those properties. But, many city counselors and residents wanted to go beyond the minimum scenario and rezone all 13 of Newton’s villages, because upzoning offers public benefits like needed housing, village vitality, and enhanced multi-modal mobility. In the end, Newton rezoned six of the 13 village centers.

After Brookline’s vote, pro-housing advocates hugged to cheer the victory over paper-compliance zoning. After Newton’s vote, many pro-housing advocates were disappointed at the loss of their more comprehensive plan. But which municipality’s new zoning makes way for more housing?

Comparing zoning across municipalities is infamously challenging. Zoning requirements can cover hundreds of pages. Figuring out what they actually allow on any given parcel of land is a big task; figuring out what they allow in total across whole districts is a next-level perplexer.

But then, remarkably, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts invented, as a part of the MBTA Communities compliance guidelines, a new concept called zoning capacity to compare zoning districts across municipalities, to serve as a standard—a performance metric—for measuring the size of zoning districts. And just as remarkably, the new measuring system has worked in implementation. Municipal planners and planning consultants are plugging into a spreadsheet simple metrics related to their zoning districts, such as minimum lot size requirements, maximum height allowances, floor-area-ratio (FAR) allowances, minimum open space requirements, minimum setback requirements, and parking requirements—and the spreadsheet communicates with a map of parcels—and then yields a capacity number for the districts in question. Zoning capacity counts how many multifamily dwelling units are allowed by zoning across all of the existing properties in a district, regardless of what is currently on those properties or what development the market might favor.

The difficulty remains, though, that the zoning capacity number does not tell us how many homes are likely to be built—because, for example, it can count “allowed housing units” in places already built as densely as the zoning allows, like with Brookline’s fallback zoning. Also, the zoning capacity number is meant specifically to help assess compliance, in broad strokes; it has not been developed as a tool for land use planning generally. A zoning capacity number is not a legal guarantee of how many housing units are allowed to be built on a given parcel. The spreadsheet might say your parcel of land has a capacity of six dwelling units, but when you puzzle through all of the requirements that apply to your property, you might find out that only three units will actually fit. On the other hand, the zoning might allow fourplexes on properties where duplexes might generate more profit.

As a novel concept, zoning capacity has led to some misunderstandings. A Newton resident just this week commented on a public Facebook conversation that the MBTA Communities law “requires Newton to add at minimum 8,330 units. It’s rather hard to gloss over that number.” This is just wrong, even though the sentiment keeps reverberating.

Per the state law, Newton’s zoning needs to allow that many units, but across parcels that are mostly built upon, many with buildings in excellent shape, many already containing multifamily housing. It is a super wonky distinction—like, if a triple decker exists, doesn’t that mean it is “allowed”? In this case, no. If the parcel that the triple decker sits on is zoned for single-family-only, then the building is considered “pre-existing, non-conforming,” and the zoning capacity for multifamily housing of that parcel would be counted as zero, even though the building (containing three dwelling units) is right there.

Right now, across Greater Boston, there is a whole lot of housing that exists but that is not technically “allowed” by zoning. Most actual multifamily housing is pre-existing, non-conforming. As discussed above, some municipalities can come into “paper compliance” with the state law, just by allowing what already exists, and not allowing any additional homes.

So the people want to know: How many new houses do we expect to see built in the coming decades under this new zoning? In Newton? In Brookline? In every community that passes new zoning?

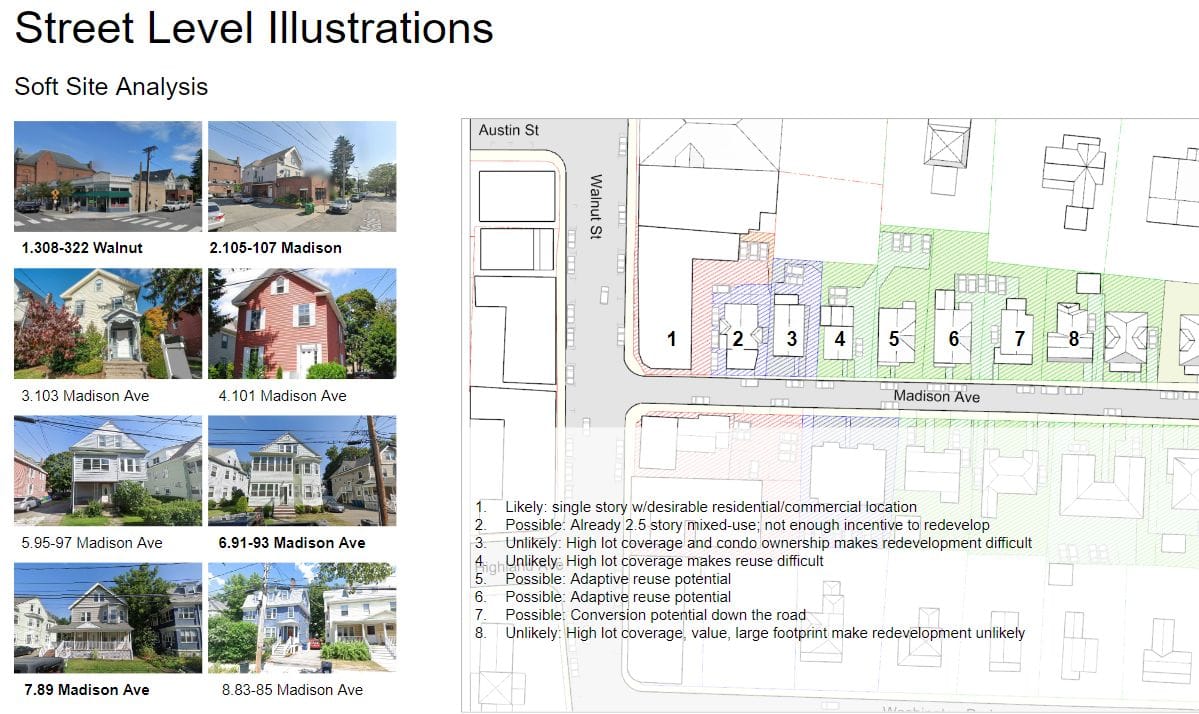

Where the new zoning for multifamily housing covers a parcel with a single-story, cheaply-built, 1950s retail box that is now sitting vacant, there is a good chance the parcel will see redevelopment. Where a parcel contains a relatively new condo building, redevelopment is highly unlikely. If municipalities want to see significant development, they can draw new zoning around parcels ready for denser redevelopment. If municipalities want to see marginal change, they can draw districts around valuable newer developments where zoning changes won’t unlock additional development potential. Many parcels represent situations between the two extremes, with varying likelihoods of redevelopment.

Each municipality is assigned a zoning capacity target as a percent of existing dwelling units in the municipality. In municipalities served by rapid transit, like Newton and Brookline, the required zoning capacity targets are set at 25 percent of existing dwelling units. Newton’s target is 8,330. Brookline’s is 6,990. Neither will get that many units through their new zoning. Entrepreneurial and energetic analysts could try to estimate expected buildouts for new districts, but we generally do not have those numbers at this time.

The thing is, to solve the state’s housing challenges, many of Boston’s suburbs will need to see thousands of homes built; they will need to meet their “capacity targets” in actual construction. The MBTA Communities law will not get us there. How far it gets us depends, in part, on how many municipalities choose the route of minimal or paper compliance, and how many go beyond the minimum requirements.

The zoning capacity targets are not construction targets for municipalities, but perhaps, in the near future, they should be.

Compliance Status Updates

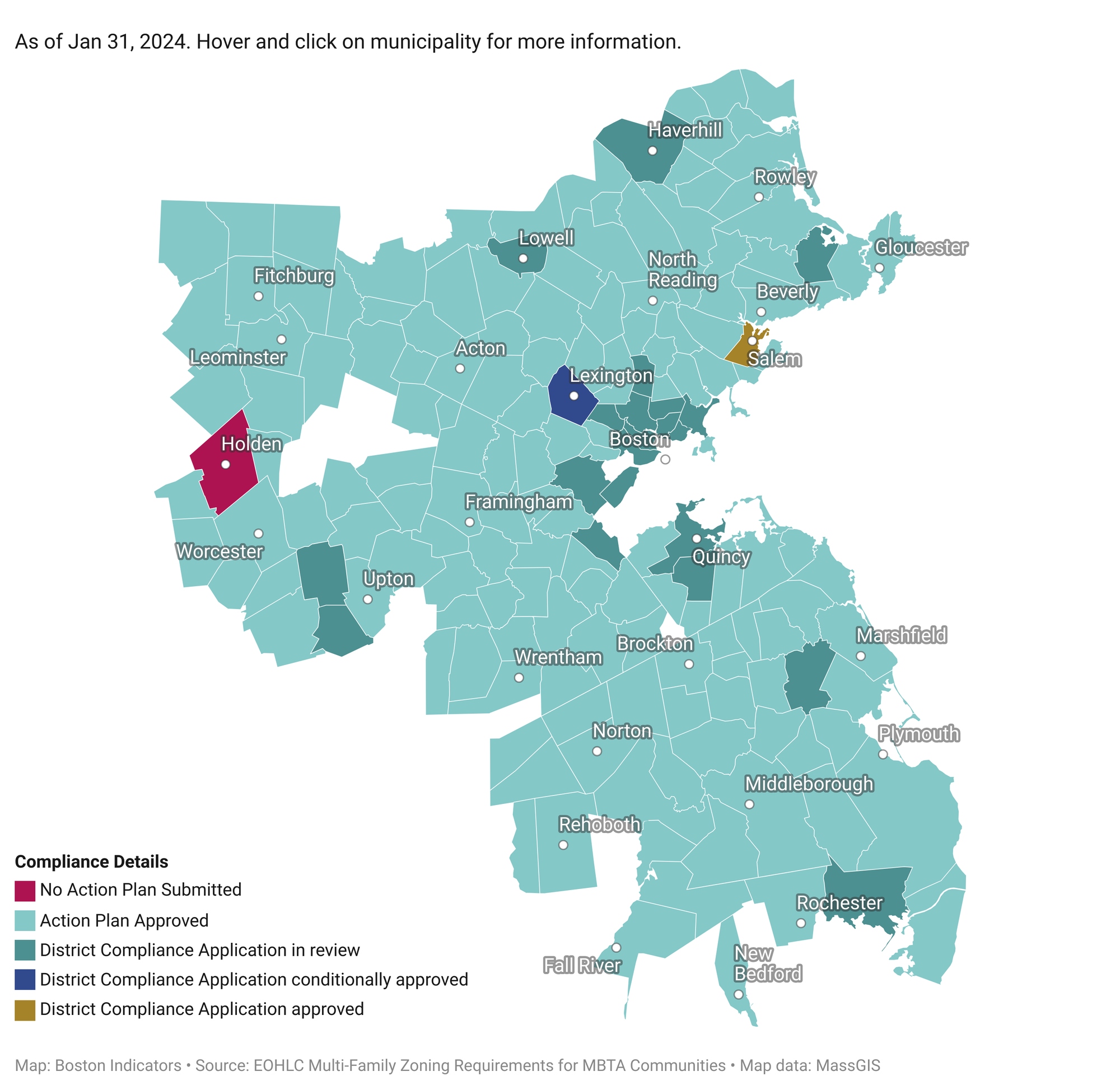

The Massachusetts Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities is posting the status of municipal applications for determination of compliance with the MBTA Communities zoning law on its website.

Relatedly, we have created a new interactive map on our MBTA Communities Tracker site that shows which municipalities have received determinations of compliance, or have submitted applications for determinations. It also provides some additional information, such as links to local 3A websites. We will update this map with new information over time.

So far, the state has approved Salem’s application, and given conditional approval to Lexington. The state is currently reviewing the applications from 11 of the 12 municipalities served by rapid transit (Braintree, Brookline, Cambridge, Chelsea, Everett, Malden, Medford, Newton, Quincy, Revere, Somerville). The status of Milton, the 12th municipality served by rapid transit, is pending Milton’s referendum, scheduled for this coming Tuesday!

In addition, Arlington, Dedham, Essex, Grafton, Haverhill, Lowell, Northbridge, Pembroke, Stoneham, and Wareham have all submitted applications for determinations of compliance, based on their zoning. The state is reviewing the applications.

Also this week Danvers voted to amend its zoning to come into compliance.

Events, Hearings, Votes

This weekend volunteers will be canvassing in Milton to get out the vote. If you are interested in joining, email Nora Harrington or Meghan Haggerty: nth02186@gmail.com or meghanehaggerty@gmail.com.

Burlington’s Working Group #2 for MBTA Communities Compliance will meet at the Town Hall Annex Basement and access via webex, on February 11, from 5:30 to 7:30 pm. The meeting will include discussion of an updated zoning map and text for the bylaw.

Sharon’s Planning Board will hold a public outreach meeting at the Sharon Community Center Ballroom, 219 Massapoag Ave., Sharon, and virtually on February 13 at 7:00 pm. The meeting link will be posted on the townofsharon.net website.

Medfield will host its second MBTA Communities Zoning workshop at the Public Safety Building on March 18 at 7:30 pm.

Belmont’s MBTA Communities Advisory Committee and MAPC are hosting their third public forum at the Beech Street Center, on February 15 at 7:00 pm. The forum is part of a community-driven effort to develop zoning recommendations for expanded housing opportunities and compliance with the MBTA Communities zoning law.

MAPC is hosting an event to explain its District Suitability Analysis Tool on Zoom on February 27, from 12:00 to 1:30 pm. This tool supports stakeholder-driven decision-making in the design of zoning districts. The tool helps municipalities within the MAPC region to identify locations that advance regional and local goals.

The Attorney General’s Municipal Law Unit is offering a training seminar on the processes of passing and filing amendments to zoning. The seminars will be held February 26 from 1:00 pm to 2:30 pm and February 28 from 10:00 am to 11:30 am.

Sherborn’s Planning Board will hold a hearing on MBTA Communities zoning amendments at Town Hall on February 20 at 7:15 pm.

Wakefield will hold a public hearing about its MBTA Communities Multi-Family Zoning Overlay District on February 13 at 7:15 pm. Information about this meeting and others can be found on Wakefield’s website. Wakefield’s proposal is to allow multifamily housing, up to three stories with no more than four units per lot, by right in the district. The plan is for Wakefield’s Spring Town Meeting to vote on the zoning.

Shrewsbury will hold its MBTA Communities Zoning Outreach Meeting at Shrewsbury Senior Center on February 13 at 6:00 pm.

Easton’s Planning Board will hold hearings at the Corona Meeting Room on February 12 at 6:30 pm and at Frothingham Hall on February 27 at 6:30 pm.

Wellesley will host a forum on Zoom on March 7 at 6:30 pm. Register online. Wellesley Executive Director Meghan Jop and Planning Director Eric Arbeene will present at the forum.

The Massachusetts Municipal Association (MMA) is hosting a free webinar on MBTA Communities zoning on February 26, from 12:00 to 1:00 pm. Attorneys Donna Brewer and Susan Murphy with the Massachusetts Municipal Lawyers Association will review the process and schedule for municipal compliance, as well as potential enforcement of non-compliance. They will also discuss the distinctions between the MBTA Communities law, Chapter 40B and Chapter 40R.

Articles, Blog Posts, and Updates

The Boston Globe’s Andrew Brinker this week wrote three informative articles on MBTA Communities. First, he highlighted Attorney General Andrea Joy Campbell’s work enforcing housing laws, including MBTA Communities. Second, he wrote a feature about Deb Crossley who led Newton’s rezoning effort. “I simply know that we as a city need to build more housing and help our village centers,” Crossley said. Third, Brinker explained that Milton could face a lawsuit if it votes down compliance at Tuesday’s referendum.

Jack Clarke and Paul Lundberg discuss why MBTA Communities zoning is good for Gloucester in this Gloucester daily times commentary.

Massachusetts Planning, a publication of the Massachusetts Chapter of the American Planning Association, featured Lowell’s MBTA Communities zoning in a 2022 article. The article explains that Lowell went beyond the state’s minimum zoning capacity requirements. The article is more than a year old, but still highlights important themes.

In December, Greg Reibman of the Charles River Region Chamber explained how Wellesley’s likely zoning approach will deliver far fewer homes than its “zoning capacity target”: “Most discouraging is that Wellesley’s proposal includes 850 units at the Nines on Williams Street. But that project and those units are already approved, a little less than half built and 90 percent occupied! That means, at best, Wellesley is creating a path for only for 583 new homes that aren't already in the pipeline. That's not likely either. Consider that many of the remaining 583 units (split between Wellesley Hills and Wellesley Square) includes parcels that may not be redeveloped for decades. Or ever.”

The regional planning agency, MAPC, is offering technical assistance to help municipalities come into compliance with MBTA Communities.

On WCVB's On the Record, Lieutenant Governor Kim Driscoll said about Milton’s referendum, "We hope it passes for Milton. We don't want to take tools away from any community." The Healey-Driscoll administration has provided nearly $6 million in technical assistance grants to 156 communities to help them comply with the law, the article notes.

In January, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston hosted a forum, now available online, on the future of the New England economy, with a focus on housing, places, and flexible work.

Arlington is considering a proposal to allow three-family homes throughout Arlington, as long as they meet already-existing dimensional requirements such as maximum height, maximum stories, and minimum setbacks.

In case you missed it earlier, check out Amy Dain’s report Exclusionary by Design, published by Boston Indicators.