Who's in charge of zoning? Implications of the Milton case for MBTA-C

Upzone Update offers analysis of MBTA-C compliance efforts, produced by zoning expert Amy Dain and the staff of Boston Indicators. This week's cover article is by Henry Korman, a lawyer specializing in civil rights, fair housing, and affordable housing development. Scroll to the bottom for a listing of news coverage and upcoming events.

By Henry Korman

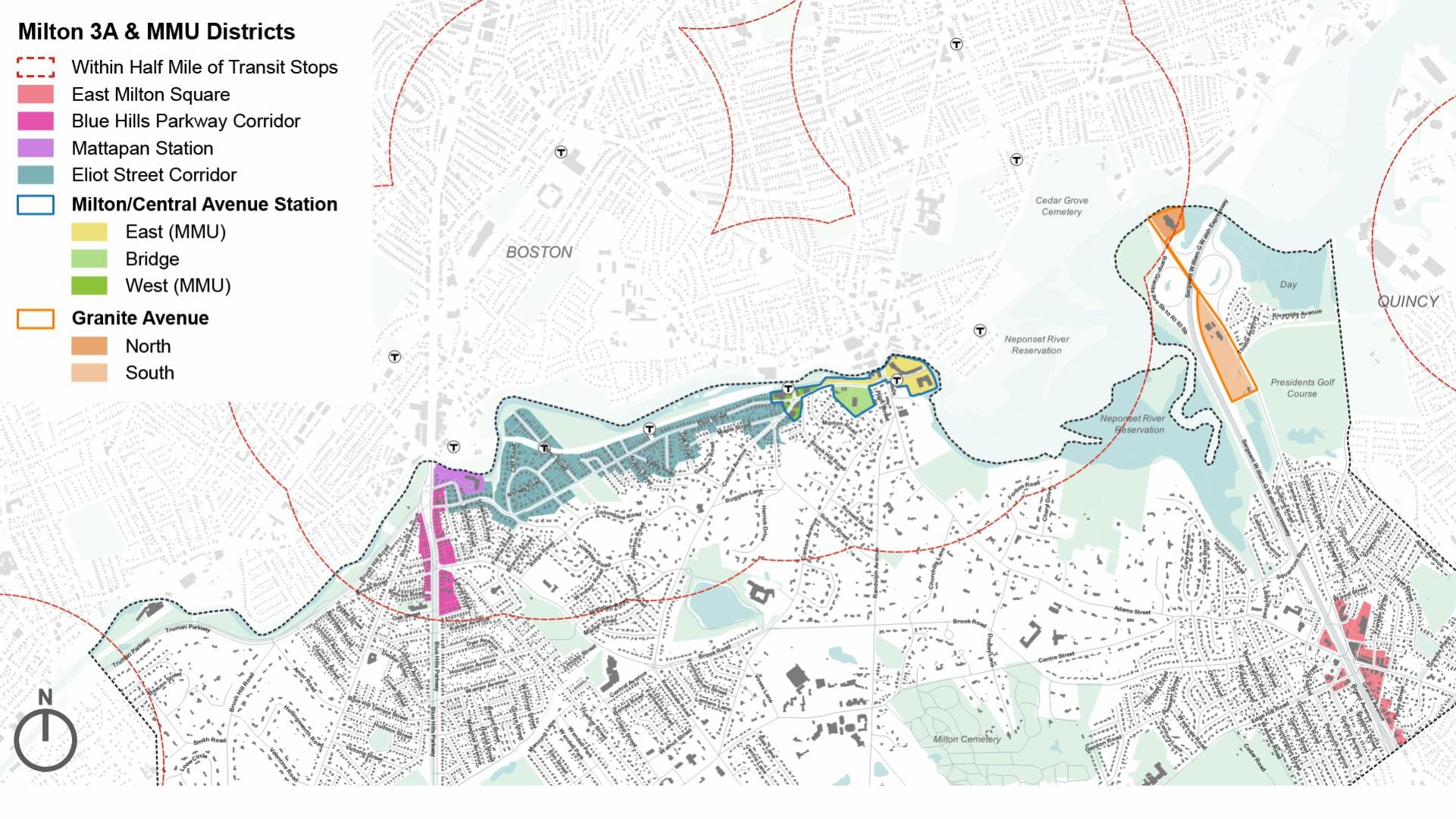

The Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) is asking two questions in the dispute between Milton and the Attorney General (AG): (1) whether the funding penalties set forth in section 3A are the only remedies for non-compliance; and (2) whether the AG is authorized to enforce compliance with section 3A by compelling the town to adopt a multifamily district? The AG’s position is straightforward. Section 3A is unequivocally mandatory. Under state law, the AG is obligated and empowered to enforce laws affecting the general welfare of the people of the Commonwealth. Milton insists on a more technical and limited reading of section 3A. To the town, the text of the statute allows only one remedy for non-compliance, suspension of eligibility for certain state grant programs, effectively allowing a municipality to opt out of MBTA zoning if it is willing to forgo the state grants. And, although the statute instructs EOHLC to issue implementing guidelines, Milton attacks the guidelines because they somehow go beyond the literal words of section 3A.

Lingering beneath the surface of the dispute are fundamental questions about the balance of power between the state legislature and local cities and towns in implementing a zoning policy designed to address a critical housing shortage that crosses municipal boundaries. These issues are not the focus of the questions posed by the SJC, or the primary focus of the written arguments of either the town or the AG. But Milton shows its hand in one short statement in its submission to the SJC, where it says that the 1968 Home Rule Amendment (HRA) to the Massachusetts Constitution “embodies a constitutional judgment that zoning ordinarily should be decided by local communities.” Taken to its logical end point, Milton claims for itself a power senior to the legislature and the ability to exercise that power solely on behalf of its residents, without regard to the needs of the larger region. As the Real Estate Bar Association’s friend of the court brief notes, the argument reflects ongoing municipal disregard for other mandatory provisions of the Massachusetts Zoning Act that have led to protracted litigation, impede the development of housing and frustrate state-wide policy goals.

In Massachusetts, zoning authority comes from two state constitutional sources. The broader of the two is the “police power,” expressed in Part 2 of the Constitution, which allows regulation of personal and property rights for the public health, safety, and welfare. In 1918, the Constitution was amended to clarify how the police power applied to land use, enabling the legislature to pass laws that “limit buildings according to their use or construction to specified districts of cities and towns.” Two years later, the General Court enacted the first comprehensive Zoning Act, delegating zoning authority to municipalities under the legislature’s strict oversight. Prior to the adoption of the HRA, only the legislature had the power to determine the extent of zoning authority granted to cities and towns, and municipalities had to strictly comply with those limits. In the words of one judicial decision, “the Legislature mandated a rule of strict compliance by the plain language” of the Zoning Act.

Milton’s formalistic and procedural arguments in the fight over section 3A stands these concepts on their head. In essence, the town’s position is that the principle of “strict compliance” now applies to the legislature, not local governments. Under this logic, if the penalty for disregarding section 3A of the Zoning Act is merely a loss of state grants, Milton is free to ignore it without further consequences. This interpretation claims more authority for the town than the HRA allows.

The HRA extends well beyond zoning. In fact, it does not mention land use regulation at all. In the relevant part, it states only that municipalities may exercise the same powers available to the legislature, provided that the exercise of that authority is “not inconsistent with the constitution or laws enacted by the general court.” Since zoning authority is already assigned exclusively to the legislature by the Constitution, a fair reading of the HRA suggests that it does not give municipalities any independent zoning power. Judicial decisions are more nuanced. They say that while the HRA grants municipalities some independent zoning authority, it does not override the legislature’s “supreme power” in zoning matters. More critically, home rule cannot be used to frustrate the legislature’s state-wide or regional land use objectives, including those expressed in section 3A.

Milton’s legal position also fails for another reason: even if the HRA grants some residual powers, those powers must still be an exercise of the police power, which is intended to serve “the good and welfare of this commonwealth”— not just the incumbent residents of a single municipality. From the beginning of land use regulation in Massachusetts, local needs have been one valid consideration in drafting zoning laws, justifying practices like single-family districts and large-lot zoning in affluent towns like Brookline, Needham, Sherborn and Edgartown. However, both before and after the adoption of the HRA, when considering some of these practices and in the context of municipal challenges to chapter 40B, the Supreme Judicial Court has also made clear that local considerations must give way when the zoning power is used “for the purpose of setting up a barrier against the influx of thrifty and respectable citizens who desire to live” in a community. And, with respect to regional needs, in rejecting Hadley’s moratorium on development, the court said that whatever “the perceived benefits” are “that enforced isolation may bring to a town facing a new wave of permanent home seekers, it does not serve the general welfare of the Commonwealth to permit one particular town to deflect that wave onto its neighbors.” In other words, where section 3A says that every MBTA community must zone for multifamily housing, Milton may not shift that responsibility to other towns simply by accepting the law’s funding penalties.

Local control over zoning has contributed to a racially and economically segregated region, where some communities restrict multifamily and affordable housing to preserve perceived local advantages. This potential was a concern of the drafters of the 1918 zoning amendment and was discussed during early municipal debates about adopting local zoning bylaws. The fact that exclusionary zoning can cause racial and economic segregation was noted by the Legislative Research Council in the 1967 report that preceded the adoption of chapter 40B. It was identified as a driver of racial segregation by the Massachusetts Advisory Council to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission in 1975. And exclusionary zoning is identified as a barrier to fair housing by virtually every other civil rights analysis carried out at the state, regional and local level since that time. Milton’s legal argument, if accepted, threatens to hinder even modest efforts to address these issues and build much-needed new housing by allowing local interests to override the greater public good.

COMPLIANCE COUNTS

Seventy-five communities have adopted zoning to comply with MBTA Communities. In total, fifty of them have submitted applications for determinations of compliance, to the state (as of September 4.) So far, the administration has issued determinations for three communities, Arlington, Lexington, and Salem. More determinations are coming soon.

Once a municipality has submitted an application for determination of compliance, that municipality is considered in interim compliance, until the state issues a further determination. Municipalities in interim compliance will qualify for grants tied to compliance. Also worth noting: the new zoning is in effect once Town Meeting or City Council approves the zoning, whether or not the new local zoning meets the specific requirements of the MBTA Communities zoning law. Property owners do not need to wait for the state’s determination to apply for permits under the new zoning.

THE LATEST NEWS

Case logistics: Six justices of the SJC will hear arguments in the Milton case on Monday, October 7 at 9:00 am, at John Adams Courthouse, Room 1. Check out the case docket for more details.

Homework: Zoning policy wonks have lots of reading: Twenty groups submitted briefs on the case to the SJC. As Commonwealth Beacon reports, three former attorneys general weighed in on whether the Attorney General has authority to compel Milton to comply with the MBTA Communities zoning law. They concluded, yes, the AG has the power to enforce state laws that pertain to the public interest.

Public opinion: MassINC Polling Group surveyed 800 likely voters, and learned that 50 percent of them consider the MBTA Communities law to be “good policy”, compared to 31 percent who view it as “bad policy.” Another 19 percent said they did not know or refused to answer.

For the sake of kids’ play: MBTA Communities is good for kids, teens included! In the Boston Globe, Jon Gorey suggests, “If we want our kids to put down their smartphones and play outside, we need to provide them with a built environment that welcomes their real-world exploration.” This means upgrading infrastructure, including wide sidewalks, public transit, car-free streets, raised crosswalks, and separated bike lanes. It also means building more housing: “Dense communities with a mix of housing options, including more affordable starter homes and multifamily apartments — such as those encouraged by the MBTA Communities law — allow more families and children to live within walking distance of each other, local parks, and public transit.” Right on, Jon Gorey.

The look of 15 homes per acre: Take a tour through this StoryMap, also by Jon Gorey, at the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy to learn about housing density in the Boston metro area.

North Shore mayors for housing: At a North Shore Chamber of Commerce event, the mayors of Gloucester, Salem, Beverly, Peabody, Newburyport and Lynn, and the town manager of Danvers, all agreed their region needs more housing. Salem Mayor Dominick Pangallo said, “Housing, without question, is the central challenge facing all of our communities right now.”

Arlington’s site plan approval: Arlington’s Redevelopment Board approved a site plan for the first time under the MBTA Communities multi-family district.

Hopkinton’s Special Town Meeting: In May, Hopkinton’s Town Meeting rejected the zoning proposal, by just eight votes -- 118 to 126. Hopkinton’s Zoning Advisory Committee voted recently to recommend three plans to the Planning Board for consideration. Hopkinton’s Select Board voted unanimously to hold a Special Town Meeting on November 18, to vote on the MBTA Communities amendment to the zoning bylaw.

Reading’s strategy: Reading’s Community Planning and Development Commission favors a plan to locate the multi-family districts along North and South Main Street and in its downtown. The strategy is to advance this proposal at Town Meeting, which starts November 12, but to have a “break the glass” emergency backup plan, called A-80, or “paper plan”, to ensure that, one way or another, Reading will reach compliance before the deadline. If Town Meeting votes down the first plan, then the Commission will “break the glass” and present the paper plan.

Attleboro, North Attleboro, Norton, Foxboro, Wrentham, Rehoboth, Seekonk, Mansfield, and Norfolk: The Sun Chronicle shares a summary of MBTA Communities zoning in all of these communities.

Southborough’s upcoming vote: At Southborough’s Special Town Meeting on September 30, there will be a vote on Article 8 that proposes allowing multi-family housing in four new districts.

Construction by Westwood’s Islington Station: One of the world’s first MBTA-Communities-permitted projects is now under construction in Westwood, 12,000 square feet of commercial and retail space along with 160 residential units, 15% of which will be income-restricted, on a former industrial site, by the train station.

FOR YOUR CALENDARS

Town Meetings are expected to take up MBTA Communities zoning proposals on the following dates:

Southborough: September 30

Manchester: October 1

Ipswich: October 22

Natick: October 15

Billerica: October 21

Needham: October 21

East Bridgewater: October 27

Ayer: October 28

Bourne: November 4

Middleborough: November 7

Medway: November 12

Reading: November 14

Millis: November 15

Winthrop: November 16

Wenham: November 16

Belmont: November 18, 19, 25

Dracut: November 18

Lynnfield: November 18

Shirley: November 18

Wrentham: November 18

Kingston: November 19

Millbury: November 19

Ashland: November 20

Bellingham: November 20

(Many more Town Meetings are anticipated. Stay tuned for calendar updates.)

City Council votes are anticipated this fall in:

Amesbury, Attleboro, Beverly, Brockton, Fitchburg, Framingham, Gloucester, Lawrence, Leominster, Marlborough, Melrose, Methuen, Newburyport, Peabody, Waltham, Watertown, Woburn

...AND AN UPDATE ON ADU POLICY

The Affordable Homes Act, signed into law this past summer, includes a provision for the legalization of accessory dwelling units (ADUs) statewide, which will go into effect in February. The new law says “No zoning ordinance or by-law shall prohibit, unreasonable restrict or require a special permit” for ADUs in single family zoning districts.

Per this law, the ADUs in question, that cannot be prohibited, are no larger than 1/2 the floor area of the main house or 900 square feet, whichever is smaller. The municipality may impose additional size restrictions and prohibit short term rental. The ADUs allowed via this law “may be subject to reasonable regulations” including septic regs, site plan review, setbacks, height limits, and max bulk limits.

For such ADUs, the municipality cannot require more than one parking space; on properties 1/2 mile from a transit station, the municipality cannot require parking at all. For such ADUs, municipalities cannot require owner-occupancy of the property.

There are lots of questions about implementation of this! The law says the state “may” issue guidelines or promulgate regulations. This is in the works. More information coming soon.

...AND ONE MORE ON HOUSINGWORKS

The new Affordable Homes Act created a HousingWorks infrastructure program, funded at $175 million, to support infrastructure that supports housing. This is especially meant to make development within MBTA Communities zoning districts feasible and functional (for housing, multi-modal mobility, and livability). But the language of the law also emphasizes that the state should consider “geographic equity” in awarding grants, since MBTA Communities zoning does not apply to significant portions of the state. The funding is not only for MBTA Communities.

Thank you for reading! We welcome your updates and insights about zoning reform. Keep sending them our way.